Why can the social memory of small nations within large multi-national states play a significant role? Because the traumatic memory of individual groups in such a complex society can be decisive in interethnic relations. Often, this occurs suddenly for the majority of society, which had previously successfully ignored it. As the German memory researcher Aleida Assmann writes in her book "Reinventing the Nation," when we talk about memory of interstate wars, forgetting can be useful for harmonizing the relationships between once-conflicting states and societies. Victory or defeat in war may be perceived differently by them, but overall, they are understood as conflicts and opposition initially on equal terms.

However, when we talk about conflicts between states and a part of their own society, especially if they were characterized by unequal power, where the state suppressed, repressed, or annihilated a helpless part of the population, forgetting will not work here. Only dialogue, acknowledgment of mistakes, and finding common ground for a shared future can neutralize the dangerous conflict potential of such memory.

Unfortunately, more often than not, states prefer to avoid dialogue, aggressively or passively ignore the memory of small groups, making it invisible to the majority. In such a situation, it doesn't disappear but continues to exist in one form or another among the descendants of the affected group, even if it disappears from everyday life. And its disappearance from public consciousness doesn't guarantee that it won't resurface in the form of post-memory among descendants during complex transitional historical periods.

This type of memory includes the history of the Circassian exile or genocide, depending on the interpretation one applies. At the level of the Russian state, it is believed that the events of the mid-19th century have long faded from memory, and any discussions on this topic are politicized attempts to divide society on a fabricated pretext. In Russian society at large, knowledge of these events is virtually nonexistent. However, within the Circassian society today, this memory, revived in the 1990s, has become a key pillar of national identity in all its layers—age, social, and gender. And the demands to speak about it loudly and openly break through, although they are suppressed by the state, sometimes in a very severe manner.

Therefore, I consider it particularly important to talk about this issue openly, clearly, and with references. Russian officials view such discussions as a form of extremism, but with such a stance, they have already brought the country to the brink of catastrophe, nullifying their own professional and moral capital. Only dialogue and candid conversation are the only correct forms of dialogue between Russian society and its Circassian part, capable of preventing severe interethnic conflicts in the future.

In this article, based on archival sources, we will delve into the details of the events of 1863 and 1864, which unfolded in the Western Caucasus and led to the catastrophe of the local indigenous Circassian (Adyghe) peoples, who were forced to flee their homeland to the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) due to the invasion of Russian Imperial forces. In the text, we will use official reports and documents from resettlement and exchange commissions, but the main focus will be on the report of General-Adjutant Count Nikolai Evdokimov, the organizer and executor of the operation that concluded the Caucasian War in such a harsh manner. Certainly, the memories we use in the text must be viewed through the prism of the subjectivity of a military official's views. These views characterize a functionary, a civilizer, and a progressive figure typical of his imperialistic era. However, it is crucial to understand that, unlike many European states, such views are still alive in Russia today and shape the thinking of a significant part of society, including the academic and governmental circles.

1.THE BALANCE OF FORCES

Before delving into the events in the Western Caucasus during the period of 1861-1864, let's examine the available statistics that will allow us to estimate the number of participants in the military actions.

Unfortunately, for both sides, we cannot definitively state specific numbers. Russian reports vary from document to document because the military operations were in an active phase with constant reshuffling of units. The composition and number of various detachments changed depending on the tasks at hand, individual military units moved between detachments, were reinforced, or, conversely, reduced. Therefore, the data presented here is approximate, based on the numbers available in the documentation and their comparisons. Based on the report of the Commander of the Kuban Region Forces, General-Adjutant Evdokimov, on the military actions in the Kuban Region for the years 1863-1864 (Source: State Historical Archive of the Republic of Georgia, fond 416, inventory 3, case №1190), we can observe the following picture of the composition of Russian troops and their losses during the campaign of 1861-1864:

The total number of troops consisted of: infantry - 58,000 people (90%), cavalry (including dragoons) - 3,600 people (6%), Cossacks - 1,300 people (2%), artillery (field and mountain guns, rocket launchers) - 34 units (0.1%), militia (Caucasians in Russian service) - 400 people (0.1%), and sappers - 800 people (1.2%). In total, there were 64,100 people and 34 artillery units.

Unfortunately, on the other side of the front, even such relative estimates are practically impossible. We can only approximate the number of Circassian men who actively resisted the advancing colonial Russian forces. Documents mention that Russian military officials conducted family-by-family statistics of all those who fled to the Ottoman Empire in 1863-1864 for the purpose of accounting for relocation expenses. However, these lists could not be found.

According to weighted estimates, approximately 750,000 people were forced to flee from the Caucasus to the Ottoman Empire during the period of 1861-1864. Another 150,000 people resettled in specially created military reserves for the local population, which Russian authorities established in the lowlands of Kuban and in the territories of the modern central part of the Republic of Adygea. Considering the low intensity of combat operations in 1863-1864 when resistance was effectively broken in most Circassian (Adyghe) communities, we can make a +10% adjustment to the total population to account for the percentage of the male population that perished in direct combat clashes with Russian regular forces.

In most documents, when counting the number of Circassian population, officials and external observers used a methodology in which one family consisted of 10 people, of which no more than 2-3 were young men. Thus, if we take the figures of 750,000 who left, plus 150,000 who remained, we get 900,000 people. Based on this number, we obtain a figure of 180,000 - 270,000 people - the male population capable of taking up arms. Taking the average of 230,000 and adding approximately 10% for those lost during the war, we arrive at around 250,000 people.

It may seem that 250,000 armed men against an army of 65,000 cavalry and infantry have the advantage. However, we must not overlook the fact that this vast mass of armed men remained at the level of training and equipment as simple militias, scattered into thousands of individual, unconnected units. The majority of them were burdened with families that needed to be hidden and protected, and in most cases, they did not have continuous military experience. In the mountainous Circassian societies, the warrior elite with experience and good equipment constituted no more than 15%, according to historians and ethnologists (according to the academic scientific book "Mentality of the Adygs in Historical Dynamics" by B.A. Trekhbratov).

The only somewhat cohesive combat units were the groups of the Ubykh communities, but their total number of armed men barely exceeded 20,000 to 30,000 people. Against the backdrop of general decline and panic in Circassian societies, their support was insufficient for effective resistance.

Furthermore, the use of the latest firearms and artillery by the Russian army, in most cases, turned the combat into a massacre in which the Circassian militias had no chance. Despite the small number of artilleries in Russian units, we can see from maps, statistics, and the memories of participants that it was precisely against those military units that were actively resisting and the remaining settlements that artillery was deployed. Meanwhile, units without artillery were engaged in reconnaissance and road construction. Typically, this pertained to infantry resistance, which was prevalent among the mountainous communities such as the Shapsugs, Natukhaits, Abadzekhs, and Ubykhs, who suffered the most in this war.

Thus, the disparity in numbers did not play a significant role in the events of the last years of the war in the Western Caucasus. We can see this in the example of the losses suffered by Russian troops, as reflected in General Evdokimov's military report:

The total casualties in the Russian forces amounted to: killed - 893 people (90%), wounded - 3,032 people, captured - 142 people, and missing in action - 50 people. In total, there were 4,117 casualties, which accounts for 0.06% of the total number of participants in the military campaign.

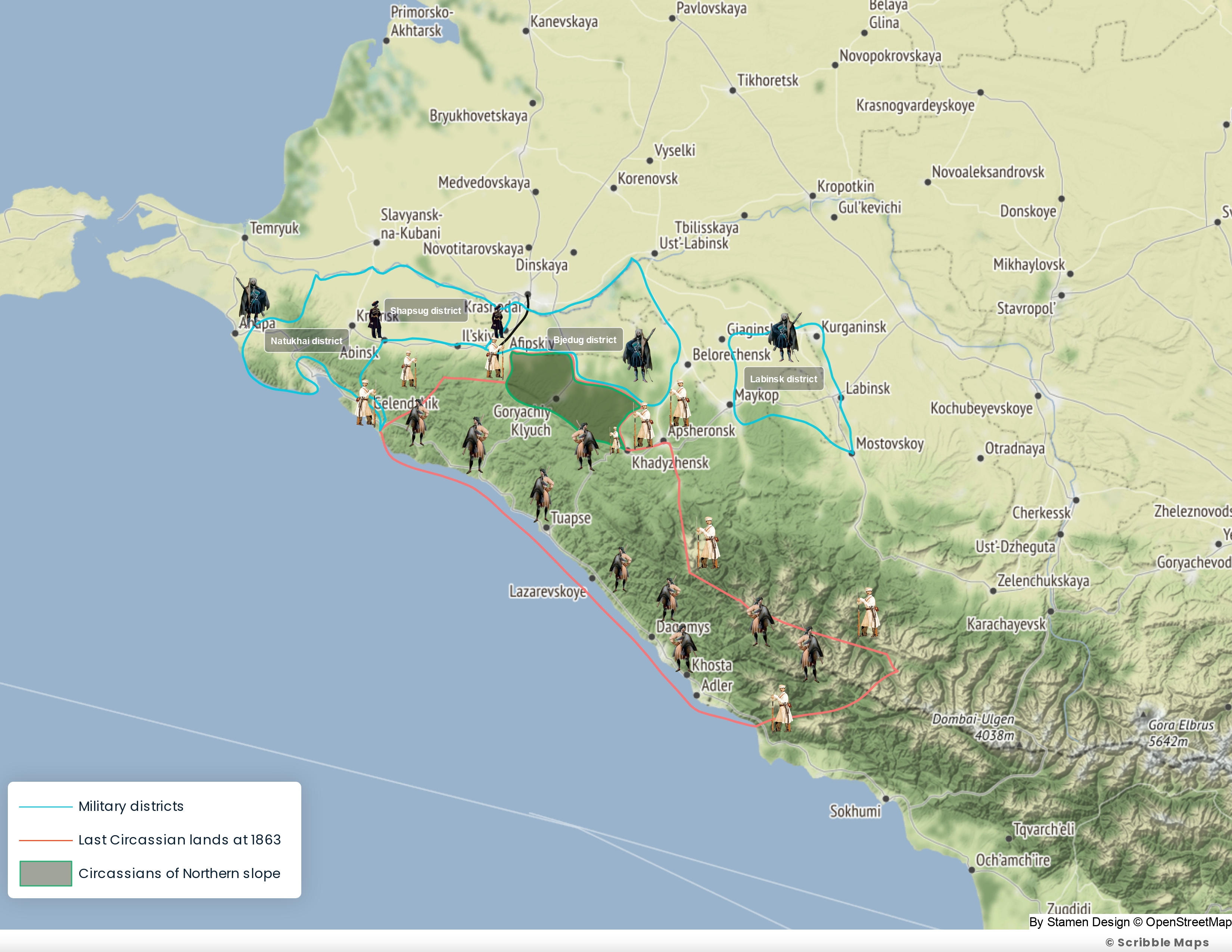

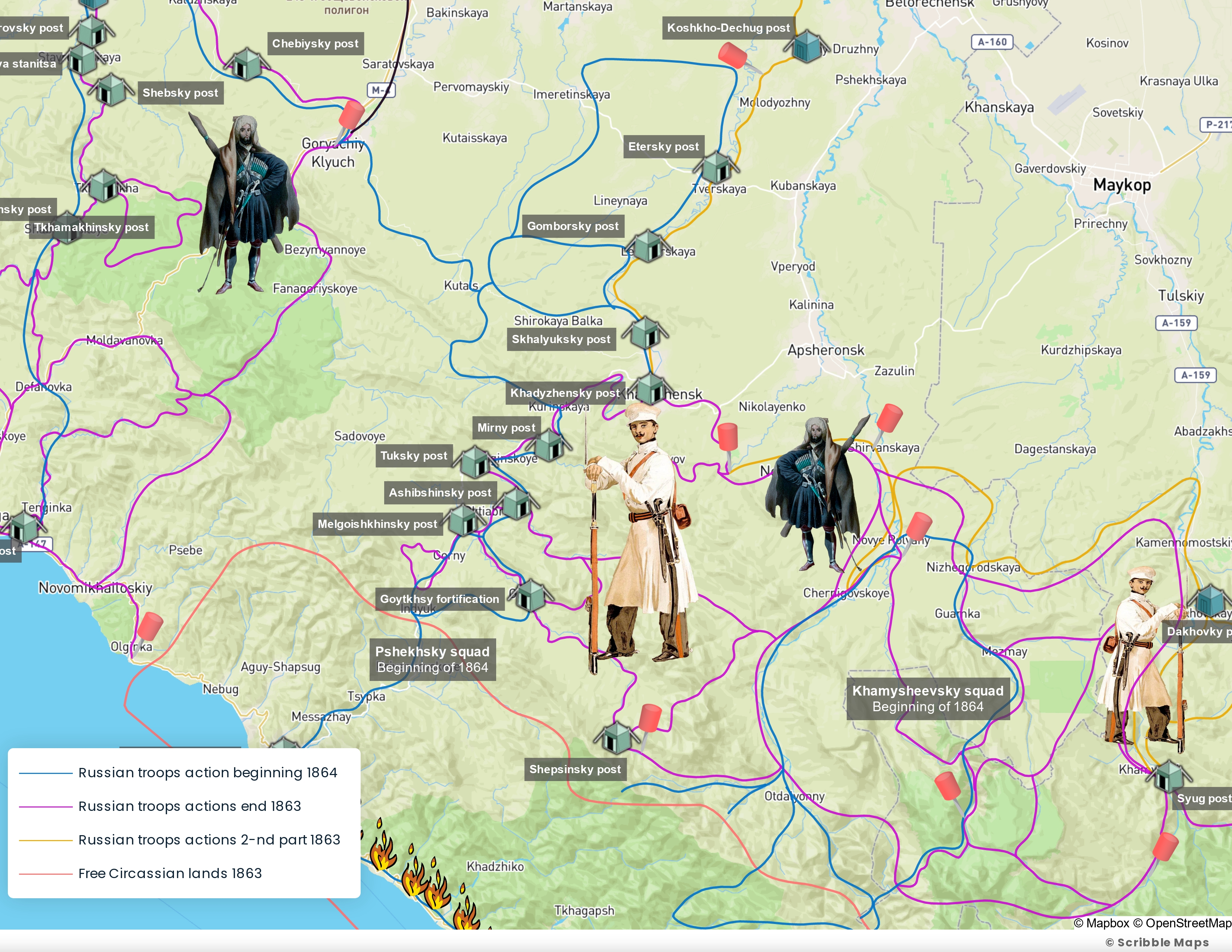

Understood, let's proceed with a detailed chronological overview of the events, which will be aided by the cartographic representation of Russian military actions in the Western Caucasus. The basis for this overview will be the Report of the Commander of the Kuban Region Forces, General-Adjutant Evdokimov, on the military actions in the Kuban Region for the years 1863-1864 (Source: State Historical Archive of the Republic of Georgia, fond 416, inventory 3, case №1190). The link will provide access to both the ORIGINAL and TRANSCRIPTION of this archival record on Russian language.

Following text in italics is reproduced from the original without changes (except for orthography), with comments from the author (not in italics).

2.CHRONOLOGY OF EXILE

The report of Count Evdokimov on the military actions carried out in the Kuban Region from July 1, 1863, to July 1, 1864, provides the following information:

The enterprises conducted in the Kuban Region from July 1, 1862, to July 1, 1863, made our position in the region stronger than ever before. By the beginning of the summer of 1863, having conquered territories along the Il’ and Mezib rivers from the Black Sea side, and from the White Sea to the Pshekha and Pshish rivers, we deprived the natives of the Western Caucasus of extensive plains and foothills with fertile soil that sustained a significant portion of the tribes on both slopes of the ridge. The remaining population on the north side of the mountains concentrated between the Shebsh and Pshekha rivers, resulting in extremely dense living conditions. The inhabitants of the Southern slopes also required an ample food supply. These results were clear not only to us but also to our adversary. Therefore, there were no unnoticed preparations for resistance, and, quite the contrary, since the occupation of the plains, the movement of the locals into our territory increased day by day.

The Ubykh people, who easily gathered significant parties of Abadzekh for attacks on our advanced settlements in 1862, in 1863 had already lost their influence over the locals on the Northern slope and began thinking about their own defense. Since the end of 1862, the more prudent elders of this people sought our attention, which served as the most reliable evidence of the decline in the enemy's strength and morale. In general, just as in the past, the mountaineers actively considered various measures to counter our forces, but starting in 1863, they began seeking a swift resolution to their situation.

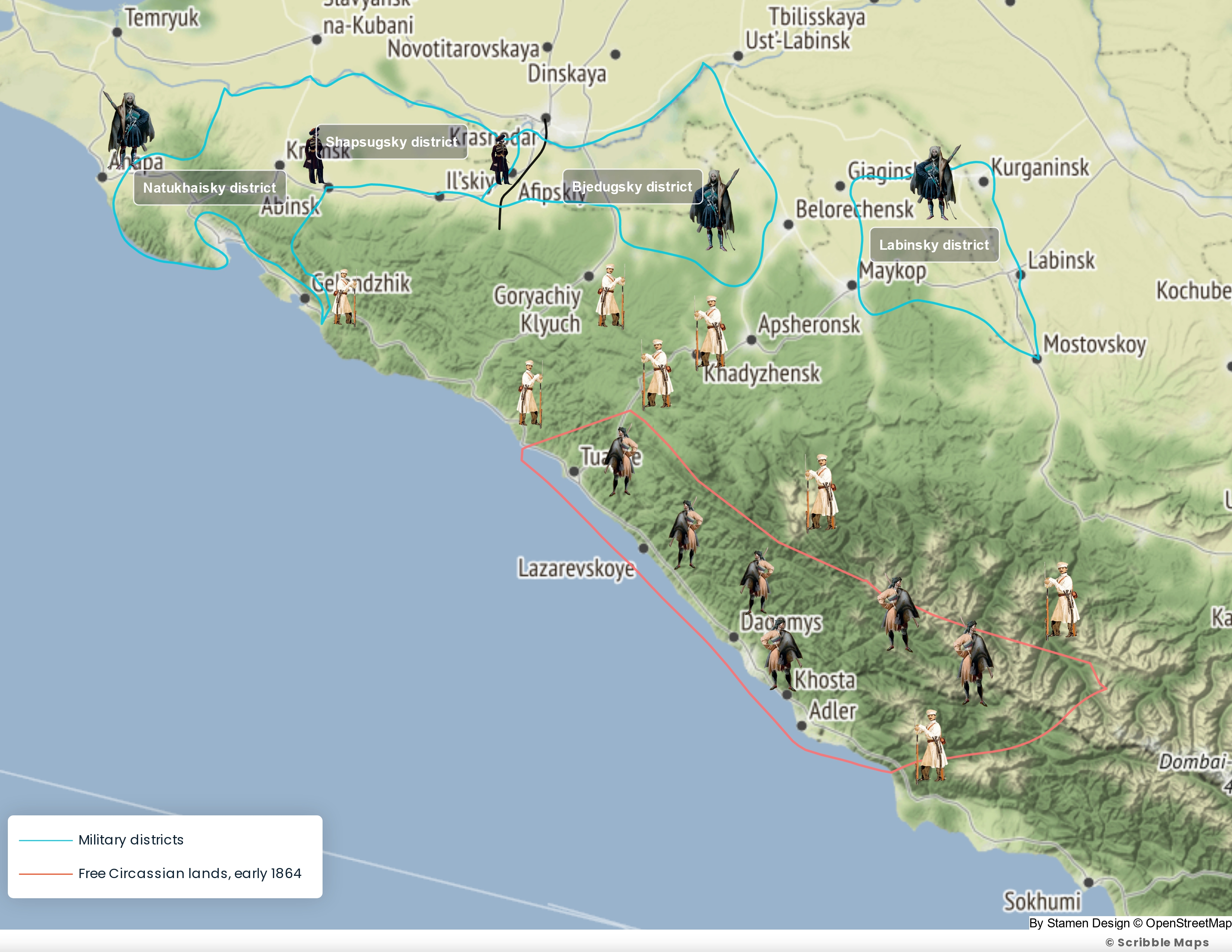

In the past, when the mountaineers, holding more or less rich foothills, decided to advance into our territory, the obedient locals living in the precincts, such as the Labinsky, Bzhedukhovsky, and Natukhaysky districts, sympathized with their fellow tribesmen, believed in their strength, and sometimes resisted the authorities. However, in the beginning of the summer of 1863, shortly after the formation of the Shapsug District, it already had a reliable militia that acted against the recalcitrant, sometimes as part of our detachments, and sometimes independently, but always carried out orders with remarkable precision.

Thus, as of July 1, 1863, our position in the Western region was as follows:

1. From the Black Sea side, we firmly established control over the territory along the Il’ and Mezib rivers, occupying the territory of the Abinsk Cossack Regiment of the Kuban Cossack Host. In the center of this territory, we prepared a reliable base for future operations, which were intended to extend to the adjacent territories of the Southern slope.

2. Our strongholds, Grigoryevskoye and Dmitrievskoye, remained as key points from the Black Sea side, connected to Ekaterinodar by a direct road established in 1862.

3. From the eastern side of the region – from the Laba and White (Belaya) Rivers, we occupied and settled the entire territory up to the Pshekha and Pshish rivers, with the latter being fortified near the Khadyzhi stronghold. An operational line was established from Pshekha, and the main depots were located at the Khadyzhi stronghold and some upper settlements on the Pshekha River. In the autumn of 1863, operations were planned to remove the remnants of the locals who still remained between the headwaters of the Pshekha and Pshish rivers.

4. Finally, separate detachments, moved upstream along the White (Belaya) and Little Laba (Malaya Laba), secured the mountainous region on our side, between the upper lines of these rivers. By the summer of 1863, our borders had expanded: from the west along the Il’ and even Shebsh, from the east along the Pshekha; on the south, detachments were positioned near the Khable, Pshekha, Belorechensky, and Malo-Labinsky passes, some of which were explored by reconnaissance, and detailed information about these passes was collected through scouts.

In this situation, the following tasks were to be undertaken: to establish a final defense in the newly settled territories, develop roads between them as necessary, and set up border posts for communication between the settlements. Additionally, it was necessary to remove the indigenous people who remained in the mountainous area between Pshekha and Pshish and occupy the entire region between the latter and Shebsh. By doing so, the goal was to completely clear the northern slopes of hostile population and settle Russian immigrants there, thereby connecting both groups of settlements established since 1860, on the one hand, along the Laba River, and on the other hand, along the eastern coast of the Black Sea.

Simultaneously, it was planned to transfer a portion of the troops beyond the ridge and, as circumstances allowed, to begin systematic operations to occupy the southern slope, initially from Mezib. After completing the operations on the northern side, the remaining troops were to be transferred through the passes, directing them towards the occupation of the southern slopes as far as circumstances would permit, and to prepare the occupied areas for colonization in 1864.

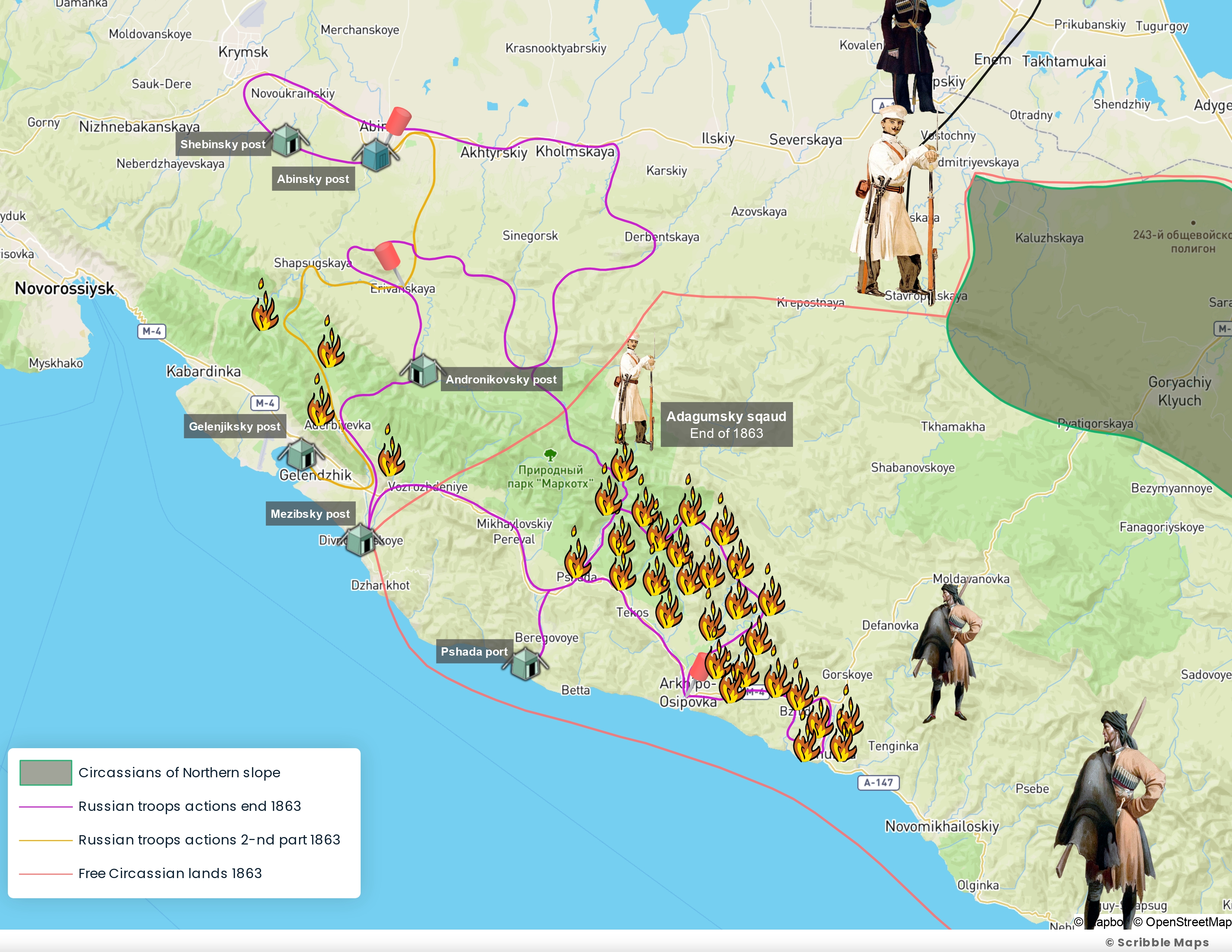

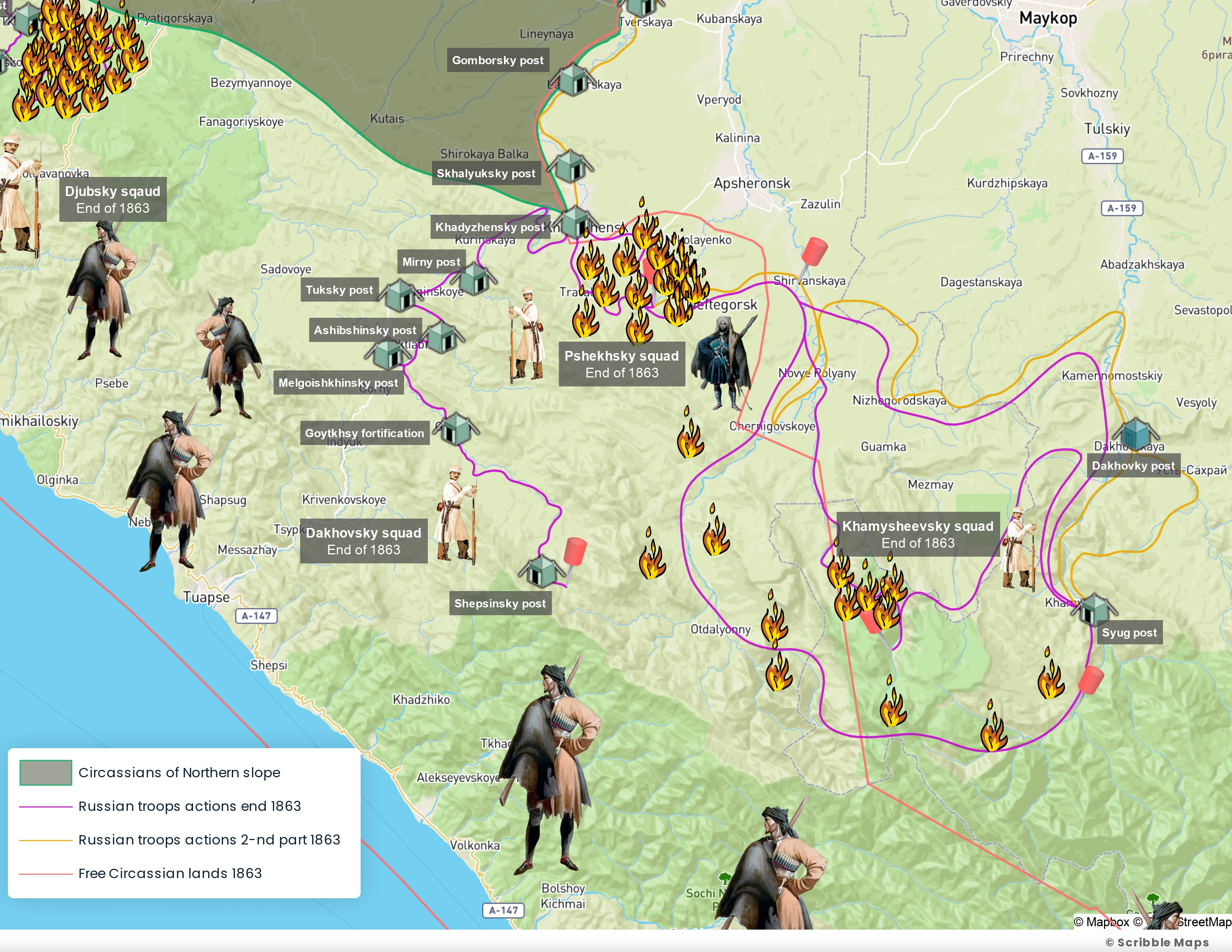

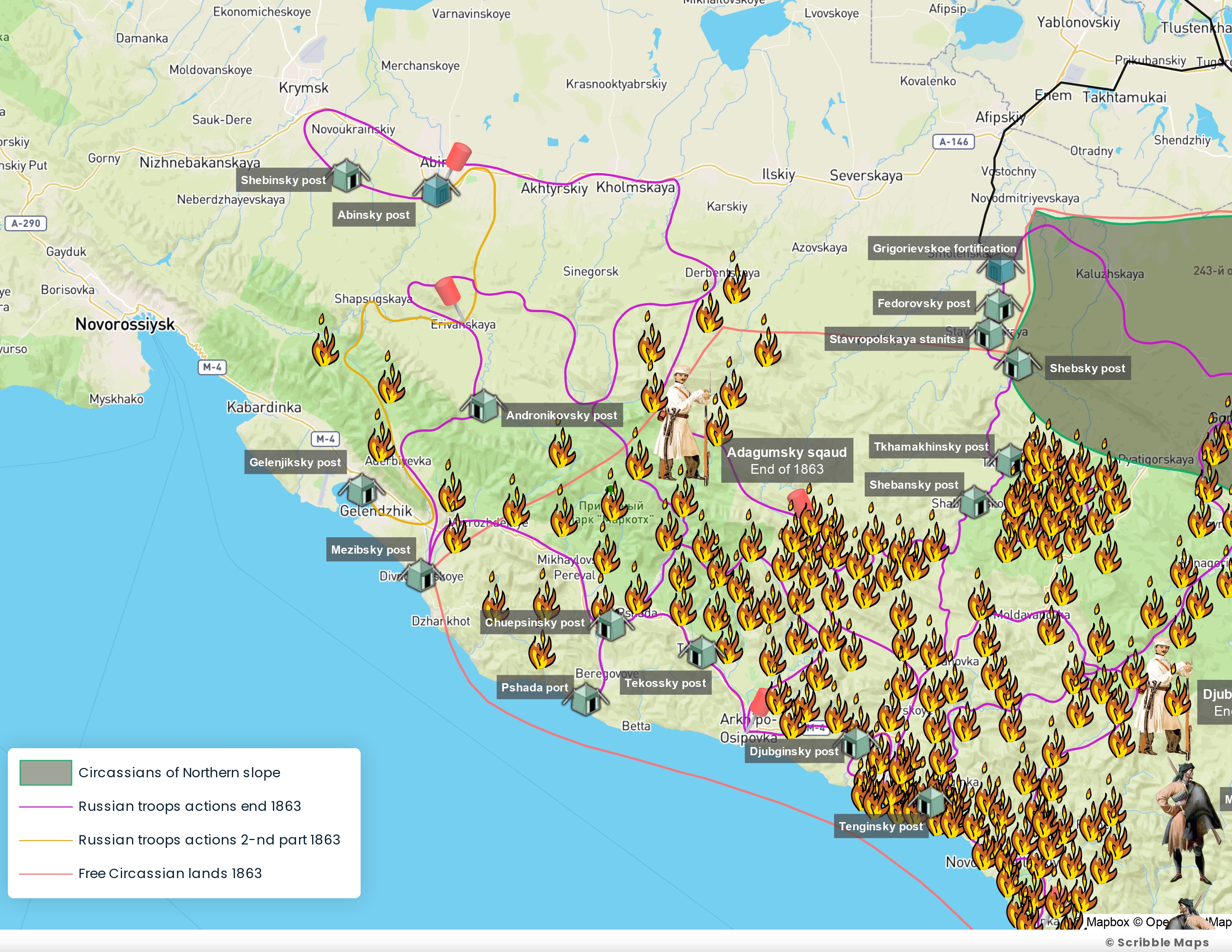

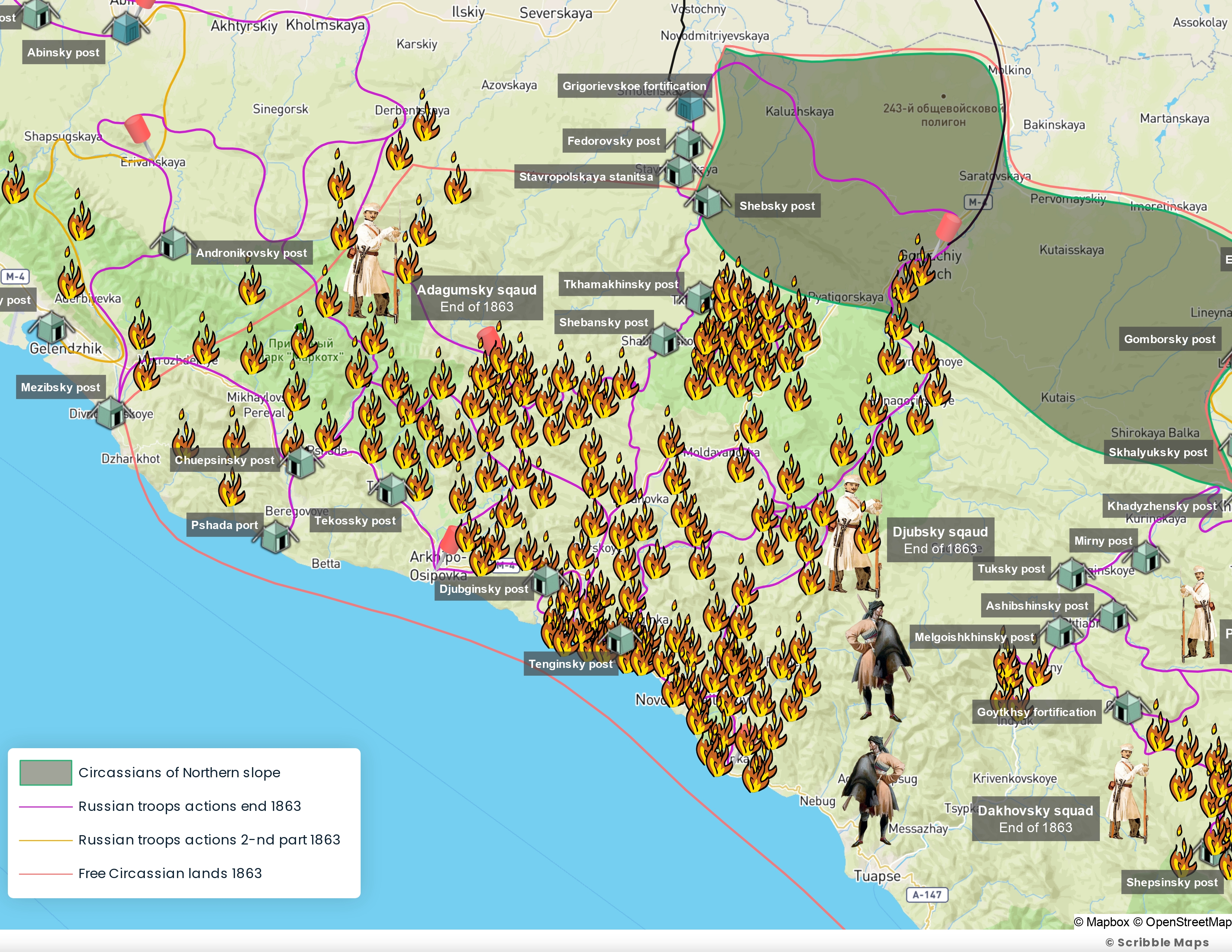

To carry out these plans, the forces of the Kuban Region and those attached to it, after setting aside the necessary troops for the defense of both existing and newly established settlements, remained distributed as they were at the end of the previous reporting year, divided into five active detachments: Adagumsky, Pshekhsky, Dakhovsky, Khamysheevsky, and Malo-Labinsky. In the autumn of 1863, to better achieve the above-mentioned objectives, a sixth detachment called "Dzhubsky" was formed from a part of the Adagumsky and Pshekhsky detachments and freed border troops. The Dzhubsky detachment commenced operations from the Grigoryevsky fortress, through the Shebshsky pass, into the Dzhuba Valley.

When, in December of that year, the operations of the Adagumsky detachment in the southern slope area extended to the region of the Dzhubsky detachment, the Adagumsky detachment was disbanded. Most of its troops were transferred to the Dzhubsky detachment, and the remainder were assigned to protect the territory occupied by the Adagumsky detachment from Gelendzhik to Dzhuba. In the early spring of 1864, the Dzhubsky detachment, having completed its program by that time, was also disbanded. Most of its troops were sent to reinforce the Pshekhsky detachment, while some remained to guard various points occupied by the detachment throughout its operations.

Before presenting a chronological account of the sequential course of actions and occupations of the troops in the Kuban Region, it should be noted that in this report, a synchronistic order of presentation has been adopted. This is because, during the course of the reporting year, the detachments, drawing closer to each other, were in constant communication, achieving results collectively and relying on each other's efforts. In contrast, in previous years, while the detachments were also directed towards a common goal, each operated under separate commands, had a more independent sphere of action, and thus, the activities of each detachment were reported separately.

The distribution of forces at the beginning of 1863

The distribution of forces at the beginning of 1863

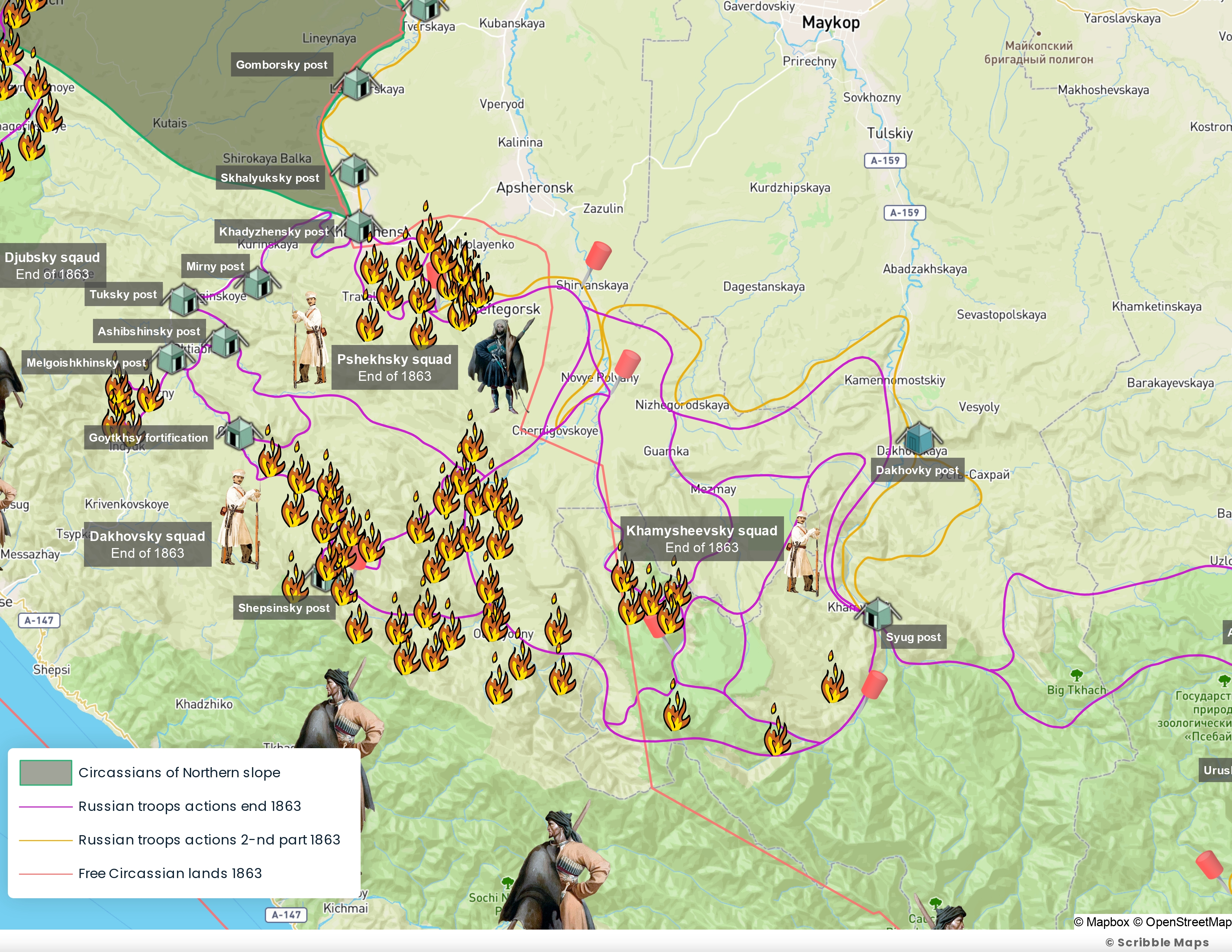

Military actions and activities of the detachments in the second half of 1863.

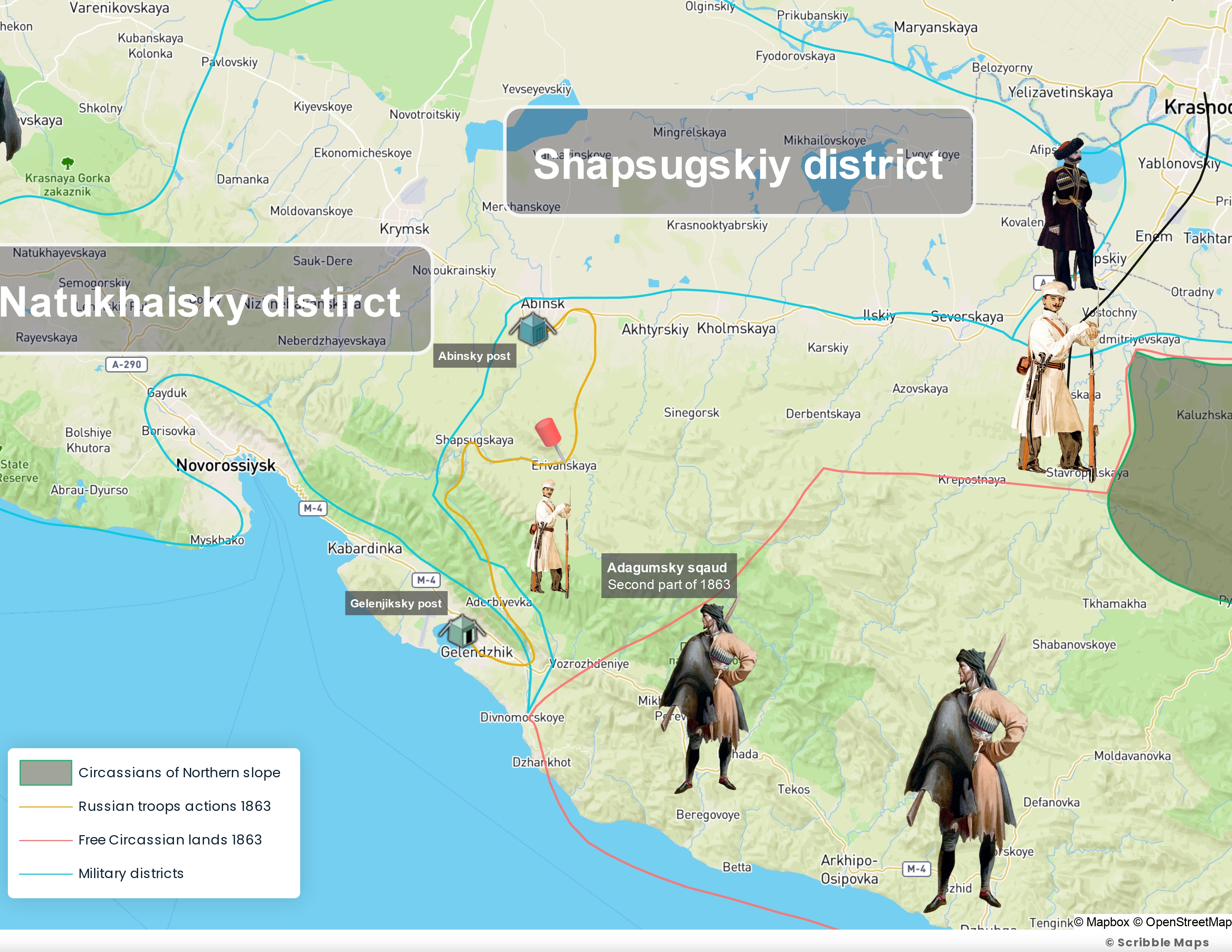

I. By the end of July 1863, the Adagum detachment, having completed the main work in the area assigned to it, the Abinsk Cossack Regiment of the Kuban Cossack Host, began preparing winter hay supplies. This was intended to provide for the government draft horses of the detachment units, as well as for specific emergency depots. By the end of July, the hay harvesting was completed, and from the 30th of that month, the detachment began building a road from the Erivanskaya stanitsa (here and therefore - Cossack’s village) through the pass and along the Aderbi gorge to Gelendzhik. In addition, a separate column established the Gelendzhik post. The detachment worked on these tasks with all its forces throughout August and the first half of September.

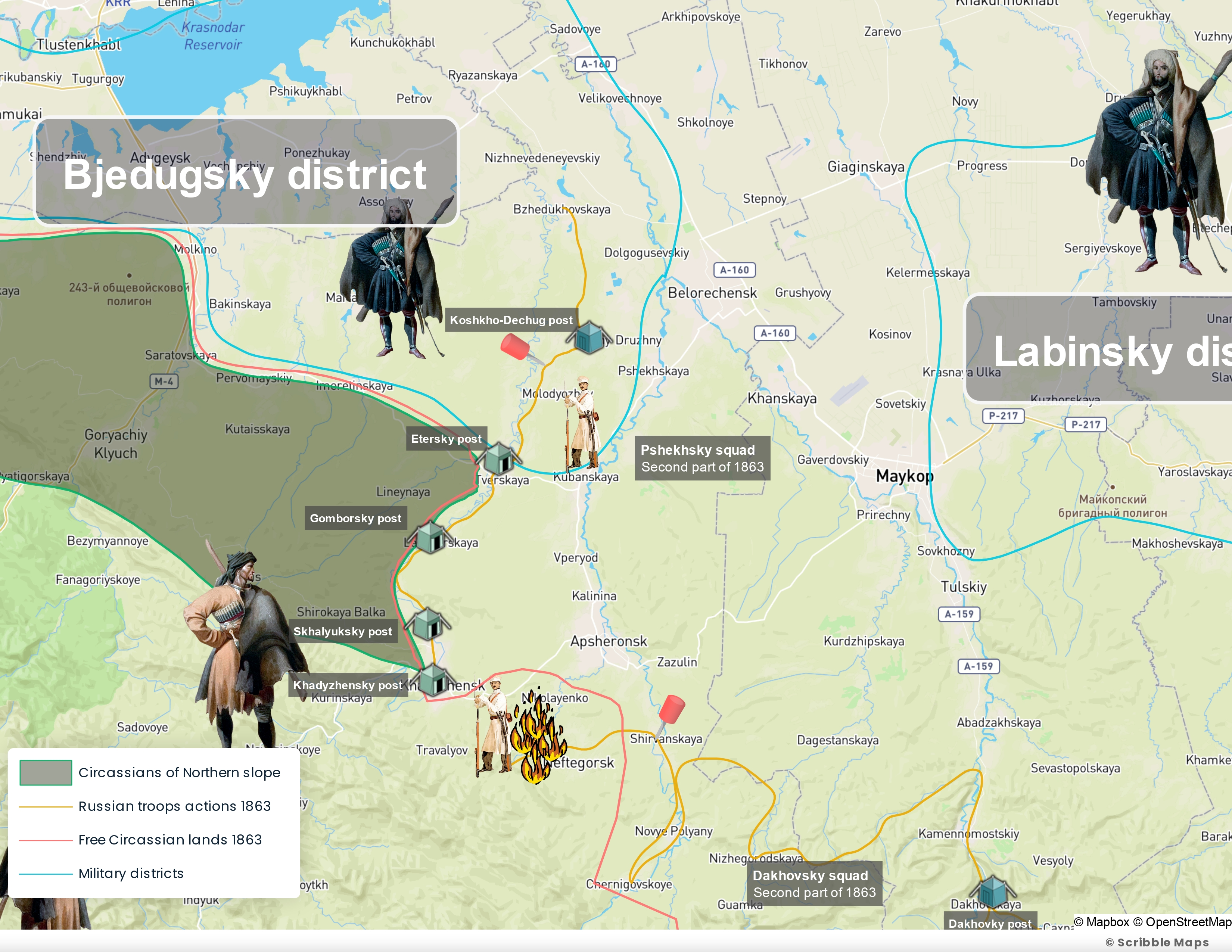

The Pshekhsky detachment, after completing the last settlements of the 26th Cossack Regiment of the Kuban Cossack Host, also engaged in hay harvesting. They started earlier and finished gathering hay by July 21st. From that time, they worked on road construction from the Koskho-Dechug post, in one direction, towards the Bzhedukhskaya stanitsa, and in the other, towards the Pshishskaya stanitsa. They also established the Eterdoksky and Gamborsky posts. In early August, the road and posts were completed, and the detachment advanced up the Pshish River to the mouth of the Skhalyuk River. They then began road construction back to the Tverskaya stanitsa and the construction of the Skhalyuk post. By the end of the month, they reached the Khadyzhi location and established this point, working on the road from the Skhalyuk post to it.

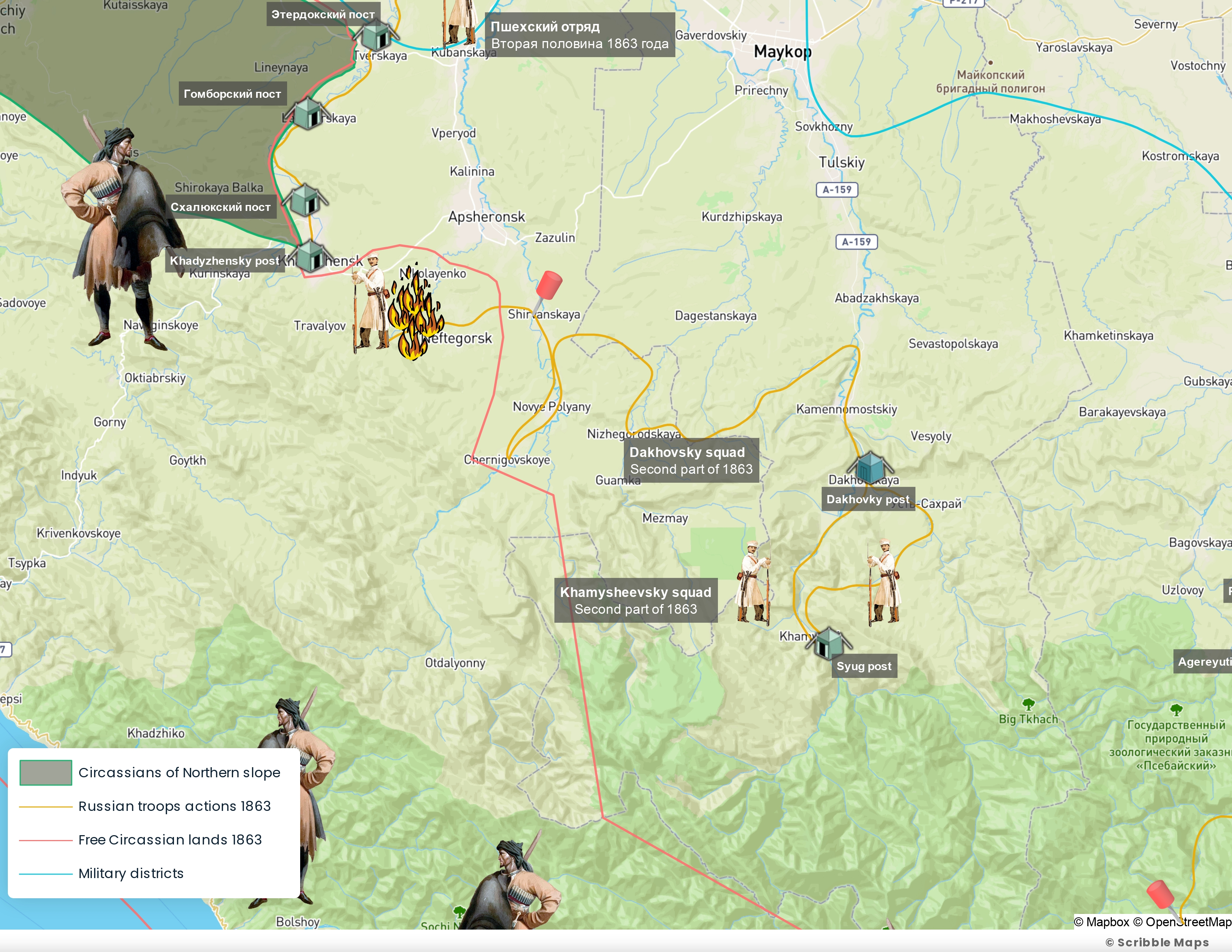

The Dakhovsky detachment spent the entire month of July 1863 on campaign activities. Separate columns were engaged in completing the posts and stanitsas at the Kurjips and Pshekha highlands. Around August 24th, these activities were completed, and the detachment, after gathering at the Shirvanskaya stanitsa, crossed the Pshekha River for operations in the upper reaches of the Pshish River. They positioned themselves on the Psekabs River, cutting a path upstream through the gorge of this river and destroying nearby auls (here and therefore – Circassian villages) near the camp location.

The Hamysheevsky detachment, formed in May 1863, had the task of developing a major road from the Dakhovskaya stanitsa up the Belaya River to the Hamysheevskoye settlement and beyond. Additionally, it was responsible for setting up a fortified headquarters for the Caucasian Line No. 3 Battalion in this settlement. During July and August of 1863, the detachment worked diligently, nearly completing the entire length of the road from the Dakhovskaya stanitsa to the mentioned settlement. By the end of August, they had occupied the Hamysheevskaya valley and established the Syugsky post at the mouth of the Syug River. Subsequently, they began finishing the road they had constructed back towards the Dakhovskaya valley.

Simultaneously, to ensure the success of this endeavor and to ease the detachment's operations in the Hamysheevskoye settlement, a temporary flying detachment was formed from the border troops of the Dakhovskaya line. This detachment descended into the Hamysheevskoye settlement from the east, alongside the Hamysheevsky detachment, following a circular road up the Lechu River from the Dakhovskaya stanitsa.

Finally, the activities of the Malo-Labinsky detachment during July and August of 1863 consisted of continuing road construction up the Shakhegyryevo gorge to the mouth of the Urushten River. They also established the Urgansky and Urushtensky posts and fortified the Agereyutinsky position. In addition to these tasks, two reconnaissance missions were conducted from August 9th to August 19th to familiarize the detachment with the areas ahead. From August 9th to 15th, one column explored the mountainous trail from the Agereyutinsky position to the sources of the Metik and Alkus rivers. The other reconnaissance mission, from August 15th to 19th, surveyed the route from the same position to the Zaagdan valley.

Actions of the Adagumsky detachment in the summer of 1863

Actions of the Adagumsky detachment in the summer of 1863

Actions of the Pshekhsky detachment in the summer of 1863

Actions of the Pshekhsky detachment in the summer of 1863

Actions of the Malo-Labinsky detachment in the summer of 1863

Actions of the Malo-Labinsky detachment in the summer of 1863

Actions of the Dakhovsky and Khamysheevsky detachments in the summer of 1863

Actions of the Dakhovsky and Khamysheevsky detachments in the summer of 1863

II. The military operations carried out by the troops in the Kuban region during the summer of 1863 placed the mountain dwellers of the northern slope in an untenable position and deprived them not only of the opportunity but also of the hope to resist us. On one hand, the Adagum detachment, having occupied the entire Shapsug plain up to the Il’ River, had already shifted its actions to the Southern slope in the valleys of Aderbi and Mezib, establishing a wheeled road there and thus ensuring the future occupation of Pshada. On the other hand, the Psekhsky and Dakhovsky detachments took control of the entire mountainous part of the region up to the Psekha River and the upper reaches of the Pshish River. The remaining unoccupied strip of land, from the Pshish to the Shebsh, surrounded from both sides and therefore vulnerable to two attacks, no longer represented a reliable stronghold for the enemy, and its fate, as we will see below, was decided on its own.

The Khamysheevsky detachment, after developing a road up the Belaya River valley, occupied the Khamyshey society and thus seized the last approaches from the Southern slope to the Belorechensk line. Independently of this, the troops of the Urupskaya border line, through repeated mountain movements, strengthened our possession of the mountainous terrain between the Kuban and the Bolshaya (Big) Laba. The indigenous people living in all these areas, partly confined to the space bounded on the east by the Pshish River and on the west by the Shebsh River, partly emigrated to Turkey, partly joined us, and partly moved to the Southern slope, and finally, in a small number, they still occupied hamlets in the valleys of Psekh and Pshish and their upper tributaries, the valleys of Shebsh, Afips, and Il’.

This state of affairs made it possible to focus the main efforts of the troops on operations to occupy the Southern slopes of the mountains, while relegating the clearance of the occupied part of the Northern plain to secondary enterprises.

In these regards, by the end of August 1863, all the troops in the Kuban region, except for the border troops, were assigned the following tasks:

a. The Adagumsky detachment was divided into two parts: the Adagumsky and Djubsky detachments. The first of them was to continue the ongoing operations on the Southern slope with the aim of firmly occupying and consolidating our presence in Pshada and for further actions to clear the Southern slope of the mountains from hostile indigenous people. The Djubsky detachment, formed at the Grigorievsk fort, consisted of 11 infantry battalions, 13 squadrons, and 3 cavalry hundreds, with 12 field guns and 8 rocket launchers. It began its operations up the Shebsh River valley with the goal of extending a convenient road to the Southern slope in the Djuba valley and establishing control over this river. The Adagumsky and Djubsky detachments, as our operations on the Southern side of the mountains continued to develop, were to coordinate their actions to completely clear the area between Mezib and Tuapse of indigenous people.

b. The Dakhovsky detachment, as mentioned earlier, crossed over at the end of August and turned its efforts towards clearing the mountainous area between Pshekha and Pshish of indigenous settlements, with the goal of finally driving the mountain dwellers away from the strip already occupied by our colonization.

c. The Psekhsky detachment, having occupied the upper part of the Pshish, initially directed its efforts towards clearing the spaces between Psekha and Pshish of indigenous people, assisting the operations of the Dakhovsky detachment.

d. The Khamysheevsky detachment, having established itself in the Khamyshey society, began work on completing the road that had been laid through the Belaya River gorge and preparing preliminary work for the construction of a fortified headquarters for the Caucasian Line Battalion No. 3 in Khamyshki.

e. The Malo-Labinsky detachment continued its ongoing operations in the Shahgireyevsky gorge, working on laying the road to the pass. In mid-September 1863, the Adagumsky detachment began carrying out the aforementioned operations. From September 15th to 19th, separate columns explored all the areas on both sides of the main ridge, from the Adagum line to Abin and Gelendzhik. A significant number of local inhabitants had returned to this area during the spring and summer, so the detachment destroyed all found supplies and structures. By September 19th, the columns had gathered at the Shebinsky post, and from that date until September 26th, they conducted movements in various directions. Initially, they moved through the forested area north of the main road, which runs from the Cossack village of Krymskaya, through Abinskaya and Antkhyrskaya, to Khablskaya. Then, they moved toward the Il’ River from this road, going up the Bugundyr, Antkhyr, Bolshoy Khabl’, and Maliy Khabl’ rivers.

On September 27th, all the columns assembled at the Andronikovsky post and, after crossing the southern slope of Kayagur, continued roadwork in the Aderbi gorge. Around October 4th, roadwork was completed up to the Aderbi River. The detachment descended through the newly constructed road into the valley of this river, reaching Mezib, where they began constructing the Mezibsky post.

During these activities, on October 7th and 8th, reconnaissance was conducted from Mezib to Pshada. Then, on October 10th, following the completion of the Mezibsky post, the detachment moved to the Zhane River. There, they spent two days constructing a road through the Vardoviye Pass. On the 13th, they advanced to the Tkhaby River, and on the 14th, they occupied Pshada. Taking advantage of their swift success, on the 14th and 15th, separate columns destroyed villages along the way as they moved up the Pshada and then crossed the elevation known as "Samochupas" into the valleys of the Tekos and Chuepsi (or Vulan) rivers.

From October 17th to 24th, the troops worked on establishing a port at the mouth of the Pshada River, fortified a camp located 4 versts (old measure = 1,06 km) from the sea coast, and conducted roadwork back to Pshada. Additionally, on the 20th, they conducted reconnaissance of a direct road to the Mingrelskaya Cossack village. By October 25th, they had completed all these tasks. The detachment, consisting of 20 infantry companies, 3 squadrons of dragoons, and one hundred Cossacks, with 2 mountain guns and 8 rocket launchers, then launched an offensive toward Djuba on the following day. Their goal was to clear the mountainous region between the Djuba and Pshada rivers of local inhabitants. On October 26th, the detachment reached Tekos, and on the 27th, they arrived at Vulan, where they stayed until November 1st, sending columns to expel unfriendly locals from nearby rivers.

As a result, on October 28th, they burned down villages in the headwaters of the Vulan River and its tributaries, Skhashtako and Netuyakh. On the 29th, they did the same along the Bzhid and Teshebsh rivers. On the 30th, they continued these actions along the Bzhid and lower Djuba rivers. Finally, on November 2nd, the detachment returned to Pshada through Vulan.

Actions of the Adagumsky detachment in the autumn of 1863

Actions of the Adagumsky detachment in the autumn of 1863

The Djubsky detachment commenced its operations on August 28th from the Grigoryevsky fortification, moving up the Shebsh River. Post Fedorovsky and Stavropolskaya stanitsa were established during this movement. The detachment was engaged in the construction of both these points and the development of the road to the Grigoryevsky fortification throughout the first half of September. On the 17th, they crossed the confluence of the Adygako and Paguko rivers with the Shebsh River, proceeding upstream through the Vachaku River via the Tsaetkh Ridge. On the same day, they advanced along these rivers to destroy existing villages along them. Then, during the second half of September and the first part of October, the troops remained in their previous positions, constructing the Thamakhinsky and Shebsky posts, procuring materials for a bridge across the Shebsh River, clearing the road down Shebsh, and developing pack road from the camp to the Stavropolskaya stanitsa through the Tsaetkh Ridge. In between these tasks, small columns were periodically formed to explore nearby areas along the Shebsh River and its tributaries, where they destroyed all the villages and their various supplies. In mid-October, a reconnaissance mission was conducted to assess the route to the pass leading to the Djuba Valley. The detachment moved in that direction on the 24th to familiarize themselves with the terrain, determine the direction, and plan further actions. On the same day, they reached the mouth of the Djuba River. On the 25th, two separate columns destroyed villages between the lower reaches of the Djuba and Shapsugo rivers, and on the 27th, the detachment returned to the Shebansky post. Starting on the 29th, they resumed their previous work.

Actions of the Djubsky detachment in the autumn of 1863

Actions of the Djubsky detachment in the autumn of 1863

The Pshekhsky and Dashovsky detachments, as mentioned earlier, completed their main tasks in the Pshekha and Pshish, and stored a certain proportion of hay in emergency depots. They began their movements at the end of August: the first detachment headed to the headwaters of the Pshish River, near the Khadyzhi locality, and the second moved beyond the Pshekha River, upstream along the Shekod River, where they took up positions. Part of the troops from these detachments remained at Kurdjipse, Pshekha, and Pshish to guard the frontiers established along these rivers.

On September 10th, a reconnaissance mission was carried out by the Dakhovsky detachment towards the peaks of the Tkhukha River, and on the 12th, the Pshekhsky detachment surveyed the area from Khadyzhi to the sources of the Tkhukha River. Detailed information was gathered about the road to the Goytkh pass and its properties. As Khadyzhi emerged as the central point for actions toward the Pshekha pass and the foothills of Psekups based on these findings, it was designated as the main depot for all combat and food supplies. It was fortified, and a temporary crossing over the Pshekha River was established.

These recent reconnaissance missions also revealed that remnants of the local population were still hiding in the local gorges between Pshekha and Pshish. Therefore, from mid-September, both the Pshekhsky and Dakhovsky detachments initiated joint operations to expel these locals.

By the end of September, the Pshekhsky detachment had cleared the region between Pshekha and Pshish, to the north of Tkhukha, while the Dakhovsky detachment cleared the area to the south of this river. Furthermore, with the assistance of flying detachments assembled from the border troops and the Kabardin militia, these detachments removed the last locals from hidden valleys in the mountainous terrain enclosed between the peaks of Belaya and Pshish.

Thus, by the execution of the final part of the overall program of operations for 1863, which aimed to clear the mountainous strip of land between Belaya and Pshish by October 1st, both of these detachments converged on September 30th and October 1st near the fortified Khadyzhi position. On the 3rd of October, both the Pshekhsky and Dakhovsky detachments, comprising 17 infantry battalions, 4 cavalry squadrons, 4 Cossack hundreds, and 1 militia hundred, along with 4 field guns and half a sapper battalion, began moving up the Pshish River to the Melgoship locality, where road development up and down the Pshish Gorge commenced on the 4th.

During this movement, at the tenth versta (approximately 10.5 kilometers) from Khadyzhi, a column of 4 battalions was left at the confluence of Shetchkar and Skaldyk with Pshish to establish a temporary fortification. Meanwhile, based on intelligence that the Ubykhs and Shapsugs gathered intended to block the detachment's progress to the Pshish pass, 8 battalions of infantry were sent to the pass on October 8th. They reached the Goytkh pass on the 9th and immediately started working on a road back down the gorge and preparing materials necessary for the construction of the Goytkh fortification and its batteries.

On October 10th, the main forces, after clearing the road to Melgoship, reached the mouth of the Sochi (Sozha) River. After reestablishing contact with the forward troops, they focused on road construction and establishing fortifications at the Goytkh position and the posts at Ashibshin, Tukshin, Melgoship, Shebsin, and Mirnoye (a temporary fortification near Shetchkar) until the end of October.

These actions finally forced the last Abadzekhs to submit. On October 4th, the most honorable elders of the lower Abadzekh arrived at the Melgoship locality and signed the proposed terms of submission. On the 6th, the same terms were accepted by the upper Abadzekhs, with the exception of one family containing around 500 households living in barely accessible ravines under the main ridge and in the peaks of Pshish. According to the conditions of submission given by them, all the Abadzekhs who submitted were allowed to stay with various restrictions and obligations in the area between Pshish and Psekups, the southern border of the Bzhedukh district, and the main ridge only until February 1, 1864. They were subject to a special overseer appointed by us. After the expiration of this period, they undertook either to move to the Kuban and Laba plains for settlement there or to emigrate to Turkey.

The Khamysheevsky detachment continued to work on the road between the Dakhovskaya stanitsa and the Khamysheevskoye Society throughout September and the first half of October. From mid-October onwards, after a reconnaissance of the Ubykh road to the pass that ascends up the Dzyshi to Mount Fisht, a part of the troops moved upstream along the Belaya River for the development of a pack road along the left bank of the river to the Pselapshish locality. They continued these works through November.

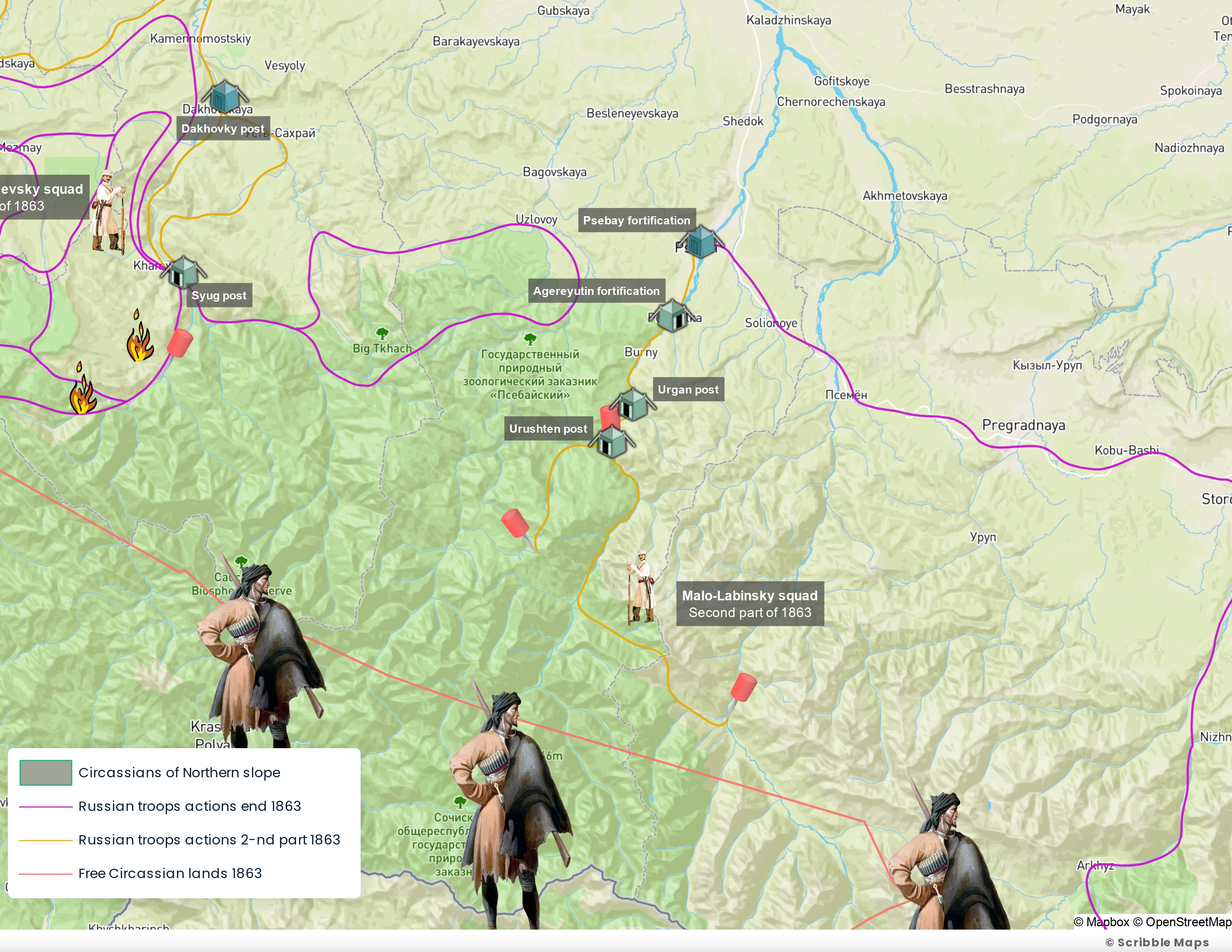

Actions of the Dakhovsky, Khamysheevsky and Malo-Labinsky detachments in the autumn of 1863

Actions of the Dakhovsky, Khamysheevsky and Malo-Labinsky detachments in the autumn of 1863

The Malo-Labinsky detachment, by November 1st, had completed the Agereyutinsky fortification and the Urushtensky post. They began constructing a permanent bridge over the Malaya Laba River at the mouth of the Urushten River. They developed one versta (approximately 1.1 kilometers) of a wheeled road from this point to the Bolshoy Rashtaishcht locality, running the road along the left bank of the river.

To ensure the thorough success of clearing the local population from the mountainous areas in the eastern part of the region, in addition to the actions of the two flying detachments mentioned earlier and in connection with the Dakhovsky detachment, a special flying detachment, departing from the Dakhovskaya stanitsa, conducted reconnaissance in the Dakhovskaya basin from September 10th to 15th. On October 2nd, two flying detachments, one from the Maykop fortification and the other from the Abadzekhskaya stanitsa, arrived at the peaks of the Khokodz River. After inspecting the local valleys between the Prusskaya and Dakhovskaya stanitsas, they reached the Samurskaya stanitsa. On the 7th, both of these detachments, along with a special detachment assembled at the Samurskaya stanitsa, arrived by different routes at the sources of the Tsitse River, where they destroyed the last remaining native dwellings.

Based on a report from the Governor-General of Kutaisi to the Commander of the Caucasian Army regarding the benefits that the presence of Kuban Region troops on the southern slope could bring to the local tribes and indicating the possibility of establishing direct communication between the Kuban Region and the Sukhum-Kale locality, in accordance with the permission of His Imperial Highness, movements of flying detachments consisting of two hundred Cossacks from the Northern slope of the Caucasian Mountains, specifically from the Storozhevaya stanitsa, took place from August 30th to September 22nd. These detachments moved over the Marukhsky pass to the Southern slope, toward the Sukhum-Kale fortification, and then returned. As there were reports of a significant enemy gathering by the time this detachment returned to the Northern slope, a column of 4 infantry battalions and half a hundred Cossacks was sent from the Malo-Labinsky detachment to the Marukhsky pass by September 20th. This column joined its detachment after passing by the returning flying detachment, which was coming back from Sukhum.

III. After returning to the Pshada camp, the Adagumsky detachment continued, starting from November 5th, to develop a road through the "Vardovie" pass and established a post there. On the 6th, they destroyed villages between Mezib and Pshada. By the 10th, they completed the post and road through the mentioned pass and crossed over to Vulan. On the 11th, they began developing a road through the "Shemozhegatl" pass and establishing the Tekos post. By the 18th, these works were completed, and both slopes of the ridge from Pshada to Shebsh were inspected. Subsequently, the detachment split into two parts.

One part, consisting of 10 infantry battalions, from November 18th to the 20th, destroyed the remaining natives between Vulan and Shapsugo. The other part, also from November 18th to the 24th, moved toward Shapsugo via the coastal road, developing the road and establishing posts at the confluence of the Bolshoy and Maliy Bzhid rivers, at the Dzhuba River, and at the mouth of Shapsugo. By November 28th, the road between Dzhuba and Shapsugo was completed. The detachment then concentrated at the Tenginsky post and on the 30th, moved towards Nedzhepsukho with several columns.

From December 1st to the 3rd, while maintaining a constant position, the troops separated daily columns to drive out the mountaineers living between Shapsugo, Nedzhepsukho, and further to the Tu River. With the Adagumsky detachment moving to Shapsugo, it entered the operational area of the Djubsky detachment. To maintain unity in the management of military operations in the area from Shebsh and Shapsugo to Psekups and Tuapse, on December 8th, the Adagumsky detachment was disbanded. Part of its forces was assigned to protect the newly occupied territory from the Dzhuba to Gelendzhik, and the rest became part of the Djubsky detachment.

By the end of December, the troops left between Gelendzhik and Dzhuba had completed the Djubsky and Chuepsinsky posts. During the first half of November, the Djubsky detachment completed the wheeled road from the Stavropolskaya stanitsa through the Tsaetkh ridge to the Tkhamakhinsky post and from there to the Shebansky post and the Tkhamakhinsky post. Additionally, a bridge was built over the Shebsh River near the Shebansky post.

To eliminate native settlements remaining in the heights of Shebsh, a separate column was sent in that direction on October 31st. After completing their mission, this column returned to the camp on November 1st.

By completing these main tasks, ensuring our possession of the entire Shebsh Valley and the surrounding area, the mobile forces of the Djubsky detachment shifted their operations to the southern slope of the Caucasus Mountains. They began efforts to firmly establish control over our region in the basin of the Shapsugo River. A raid carried out by the troops of the Djubsky detachment in late October in the Djuba and Shapsugo valleys, along with simultaneous actions by the Adagumsky detachment between Pshada and Djuba, forced the entire mass of the native population to evacuate from the Gelendzhik area and move further east towards the sources of Shapsugo and Nedzhepsukho.

To further push this population away and as much as possible clear the territory of the natives adjacent to the route being established from the Shebsh Valley to the southern slope, on November 15th, the detachment moved in three columns to the mouth of Defan. On the 18th, reconnaissance was conducted from this position to the mouth of Shapsugo, in coordination with the forces of the Adagumsky detachment. The advanced column occupied the mouth of Shapsugo on the eve of the arrival of the Djubsky detachment there. On November 25th, the Djubsky detachment descended to Shapsugo on the coast, where they, along with the Adagumsky detachment, began establishing the Tenginsky post and conducted raids in different directions by the end of November.

Simultaneously with the December movements of the Adagumsky detachment from Shapsugo to Nedzhepsugo, the Djubsky detachment, coordinating with this advance, moved in several columns on December 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th from the mouth of Defan to the peaks and middle reaches of the mentioned rivers, destroying the population. Afterward, they moved up the Shapsugo River and crossed over to the Psekups basin, clearing the left bank of this river from the natives. They then divided into two parts.

One part began to establish a temporary border line from the town of Ekaterinodar, through the Enemsky post, to the Psekups hot mineral springs. From there, they moved up the Psekups River to the Shapsugsky pass and further down to Shapsugo to its mouth. By the end of December, the first part of the detachment had moved to the Grigoryevsky fortification, while the second part remained at Shapsugo, conducting searches in the surrounding areas.

The Pshekhsky and Dakhovsky detachments, during the entire first half of November, remained in the Pshish Gorge, continuing road construction and cordoning off this gorge. On the night of November 7th to 8th, the combined forces of both detachments launched a raid into the Chilipse River gorge, where they defeated a gathering of Ubykhs. On the 17th, the Dakhovsky detachment destroyed mountain dwellings in the Gyshe-Yakub basin.

By November 20th, the Pshekhsky detachment had advanced its work to a state where they could leave their completion to a separate, small portion of troops. The rest of the forces from both the Pshekhsky and Dakhovsky detachments were turned towards driving out the natives who had settled in temporary dwellings between the Pshekha and Pshish rivers, as well as in the areas between these rivers.

On November 28th, the Pshekhsky detachment, consisting of 5 infantry battalions and 2 hundred Cossacks, with 2 mountain guns, moved from the Ashibshinsky post up the Sozha River. After traveling along the entire length of this river, they crossed over to the peaks of the Pshish River. On the 29th, they arrived at the Goytkh fortification and resumed road construction. Extremely deep snow, severe cold, especially fierce blizzards throughout December, made it impossible for the detachment to carry out offensive actions. The Pshish Gorge, filled with snow, forced them to retreat to Khadyzhi, and by January 1st, the troops had reached the mouth of the Otsepsyp River.

The Dakhovsky detachment was sent to clear the upper reaches of the Pshekha River. Before the execution of this mission, a separate column of their detachment arrived in the Samurskaya stanitsa on November 26th, consisting of 3 infantry battalions and 2 mountain guns. This column moved upstream along the Pshekha River, meeting the Dakhovsky detachment descending along the Kusha River. To ensure the success of this operation, a flying detachment of 4 infantry battalions, 4 squadrons of dragoons, and 5 hundred Cossacks was dispatched from the Kurjips area. After completing road construction by November 28th and fortifying the Goytkh fortification, the Dakhovsky detachment, consisting of 6.5 infantry battalions and 1 hundred Cossacks, with 4 mountain guns, moved upstream along the Pshekha River. They then crossed over to the Sotzepsi River, and on December 1st, they crossed from the Sotzepsi to the Kusha River, descending on the Pshekha River. Simultaneously, a column, previously directed to the Samurskaya stanitsa, approached the northern exit of the Pshekha Gorge. The flying detachment, after crossing the Tsytsa River, was stationed at Chikhupse. Until December 7th, all troops engaged in cutting paths and developing pack trails here. On this day, they descended to the Samurskaya stanitsa, and for the rest of December, they worked on improving roads and bridges between the stanitsas located in the upper reaches of the Kurjips and Pshikha rivers.

The Khamysheevsky detachment, during November and December, continued its road construction, prepared wood for a bridge over Aruan, and conducted six reconnaissance missions in the mountainous areas between Khodzh and Belaya. Specifically, on November 4th, they moved northwestward towards the Asekh Mountain to the Argozhi area, then through Azhinokh to the Pshekha River and the Gech River, and further through Kun to Achizhbok. On the 9th, they surveyed the heights of Guam and the Mezmaevskaya basin. On the 11th and 12th, they traveled upstream along the Belaya River to Telyapshish, and on the 13th and 14th, they explored the area around Azhinokh and further upstream along the Chesu River.

The Malo-Labinsky detachment, in November and December, continued to build a permanent bridge over the Malaya Laba River at the mouth of Urushten and worked on the road to the Bolshoy Rashtaikht area. In addition to the movements undertaken by active detachments during November and December, special flying detachments from the border troops gathered in various parts of the region. They inspected the folds of both slopes of the main ridge, destroying remaining isolated settlements and dwellings of the mountaineers and capturing wandering families and marauders. In this way, to explore the areas between the Belaya and Pshekha rivers, a flying detachment set out from Maykop on November 12th, reached the Nizhegorodskaya stanitsa, and, after joining forces there with a flying detachment assembled from troops located in the upper reaches of the Kurjips and Pshekha rivers, explored the Mezmaevskaya basin and Guaborabgo. To provide details of the inspection of the areas adjacent to the mountain stanitsas of the Labinsky Regiment, a flying detachment moved from November 11th to 18th, between the heights of Khabl’, Pshada, Afips, and Ubin. They explored the area from November 12th to 18th, from the heights of Guamo and the Mezmaevskaya basin, and from November 9th to 17th, they went upstream along the Belaya River to Telyapshish. From December 1st to 11th, a flying detachment, assembled in the Il'skaya stanitsa, destroyed part of the mountain dwellings in the upper reaches of Il’, Shebsh, Psekups on the northern slope, Nedzhepsugo, Shapsugo, and Djuba on the southern slope. From December 10th to 17th, a flying detachment, assembled in the Khablskaya stanitsa, surveyed the peaks of Khabl’, Pshada, Afips, and Ubin. On December 30th, a flying detachment made a raid into the valley of the Kusha River from the Samurskaya stanitsa.

Actions of the Adagumsky detachment in the end of 1863

Actions of the Adagumsky detachment in the end of 1863

Actions of the Djubsky detachment in the end of 1863

Actions of the Djubsky detachment in the end of 1863

Actions of the Dakhovsky, Khamysheevsky and Malo-Labinsky detachments in the end of 1863

Actions of the Dakhovsky, Khamysheevsky and Malo-Labinsky detachments in the end of 1863

Actions of the Malo-Labinsky detachment in the end of 1863

Actions of the Malo-Labinsky detachment in the end of 1863

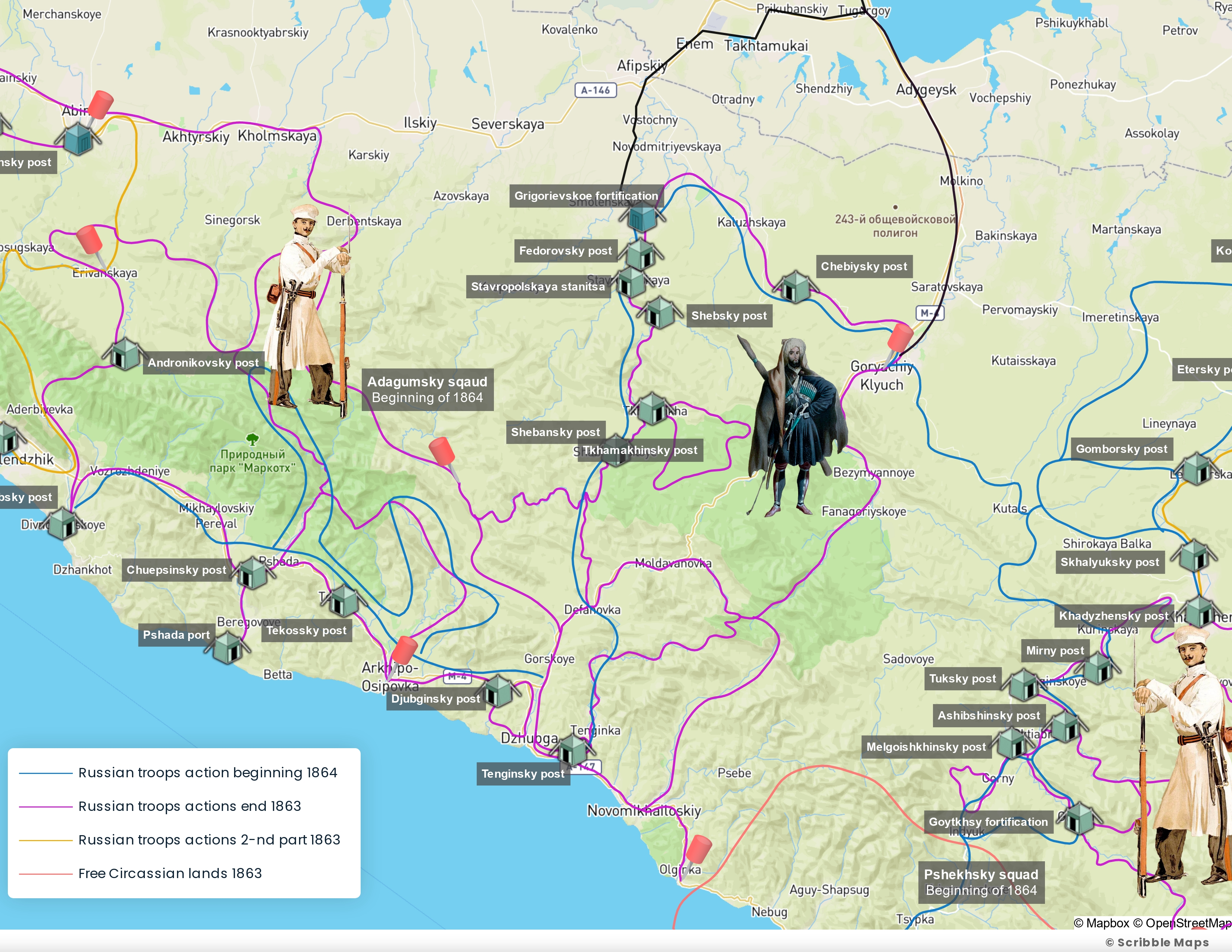

Military Operations and Activities of the Detachments in the First Half of 1864.

I. During the month of January 1864, the troops assigned to protect the newly occupied territory from Djuba to Gelendzhik conducted several movements into the mountains in different directions to investigate whether there were any remaining mountain dwellings in the ravines. Specifically: on January 18, a movement took place from the Chuapsinsky Post between Mezib and Djuba. From January 20 to January 30, movements were conducted through the ravines of Pshada, Vulan, and their tributaries.

Deployment of Military Detachments at the Beginning of 1864

Deployment of Military Detachments at the Beginning of 1864

Military Actions and Activities of Detachments in the First Half of 1864.

In January 1864, the first part of the Djubsky detachment, which had moved towards the Grigoryevskoe fortification in the first half of December 1863, completed work in the vicinity of this fortification. On January 2, 1864, it moved towards the Psekups mineral springs but concentrated there only on the 6th due to heavy snowfall and blizzards. On the 8th, it began to establish the Chebiysky post. Simultaneously with the Djubsky detachment, the Bzhedug militia arrived at Psekups, making a raid into the Tfiako gorge on January 7.

While the Dahovsky detachment was carrying out its movement towards Kusha, it had to inspect a small valley in the Pshekhs mountains where the so-called Mountain Tubin Society lived. It was necessary to destroy the auls of this last refuge for the as-yet un-subdued natives of the Northern slope.

For this purpose, in the Samurskaya stanitsa, three infantry battalions, four squadrons of dragoons, and thirteen Cossack hundrends, along with two mountain guns, were concentrated. On January 8, these forces moved up the Pshekha River, overcoming tremendous difficulties due to heavy snowfall, and by the 10th, they had occupied the Tubin Society, where they destroyed some auls and conducted reconnaissance of the Ubykh pass and several other routes leading out of the Tubin Society in various directions. The severe winter forced the detachment to return to the Upper-Pshekha stanitsas on January 12, where they continued the same work as at the end of 1863.

The Pshekhsky detachment, having arrived at the mouth of the Ocepcep River on January 1, began cutting a path between the Zhips and Ocepcep rivers, building bridges on the left tributaries of the Pshekha, developing a wheeled road between Khadyzhi and the camp, and constructing a fortification on the right bank of the Ocepcep River near the mouth. A separate work column repaired sections of the road and bridges between the Pshishskaya and Pshekhskaya stanitsas.

By mid-month, the bridge across the Ocepcep River was completed, making it possible to conduct reconnaissance of new terrain towards the Psekups, thus indicating to the Abadzekhs our firm intention to send them away in early February, i.e., immediately after the expiration of the term given to them for temporary residence in their places, between the Pshish and Psekups. On January 15, the detachment moved up the Ocepcep River and, after covering 13 versts, camped at the Tsytse River. On the 16th, it continued towards Khatost but, due to heavy snowfall, returned after covering 2 versts to the mouth of the Khataramuko River. On the 17th, three battalions were cutting a path along the road to the upper reaches of the Ocepcep River, after which the detachment moved back to the mouth of this river and, starting from the 20th, began clearing the snow in the Pshekha Gorge to open up at least some temporary communication along this gorge.

With the deadline for the relocation of all Abadzekhs who had been temporarily settled between the Pshish and Psekups rivers approaching, they were ordered to begin evacuating immediately. They were given a seven-day period to gather their belongings and remove them from their auls. Then, the Pshekhsky and Djubsky detachments were directed to the area between the Pshish and Psekups rivers, and the Dahovsky detachment to the upper reaches of the Pshish River to inspect their respective areas. They were tasked with verifying whether everyone had been evacuated, and if any auls still occupied by Abadzekhs were found, they were to be immediately evacuated.

In execution of these orders, on February 8th, the Pshekha detachment crossed to the left bank of the Pshish River and moved towards the Marta River in several columns. They thoroughly searched the area between this river and the Pshish in different directions, evacuating all the lower Abadzekhs living in this region.

Simultaneously with these actions of the Pshekha detachment, the first column of the Djubsky detachment crossed to the right bank of the Psekups and, with the same goal as the Pshekhsky detachment, moved towards the Marta River. Acting in coordination with the Pshekhsky detachment, they evacuated the lower Abadzekhs from the area between this river and the Psekups by the 16th.

The Dahovsky detachment, concentrating at Khadyzhi on February 10th, consisting of 11.5 infantry battalions and six mountain guns, inspected the side ravines of the Pshish Gorge until the 17th, driving out all the natives. Upon reaching the Pshish Pass, the detachment camped below the Goytkh fortification for further actions on the southern slope of the mountains.

Thus, by February 20th, the last natives of the Northern slope, who had remained in their previous locations, were either sent away, in accordance with the permissions granted to them, or were hiding in the mountainous terrain. Part of them was resettled in the specified locations in Kuban and Laba, and others were sent to various points along the coastal area for eventual resettlement in Turkey. Those individual families that were still wandering in the hidden ravines of the main ridge, where the troops had no time or opportunity to penetrate, as well as the surviving part of the Mountain Tubin Society, were in a blockade-like situation, as the entrances and exits were blocked by massive snowdrifts. Thorough clearing of such areas was carried out, as we will see below, by light columns and neighboring border troops.

In addition to the actions described above, the Dahovsky detachment still had the task of removing the upper Abadzekhs who lived in the depression formed by the upper reaches of the Psekups River, between the main ridge and the Kotkh ridge. This task was accomplished by this detachment with the assistance of a part of the Djubsky detachment by March 1st. On the same date, the Pshekhsky detachment crossed the main ridge via the Psekups Pass and, entering into coordination with the actions of the Dahovsky detachment, which will be discussed below, cleared the peaks of the Tuapse River and arrived at Khadyzhi on March 17th.

These February actions of the Djubsky, Pshekhsky, and Dahovsky detachments marked the end of the actual military operations in the Northern slope, and in the same month, positive actions were initiated on the other side of the mountains. It was decided that the Dahovsky and Djubsky detachments would begin these actions. The first detachment was to cross the Pshish Pass, occupy the Tuapse River valley, and the second detachment was to facilitate the advance of the first by moving across the pass into the Shapsugo valley and from there to the mouth of the Tuapse River.

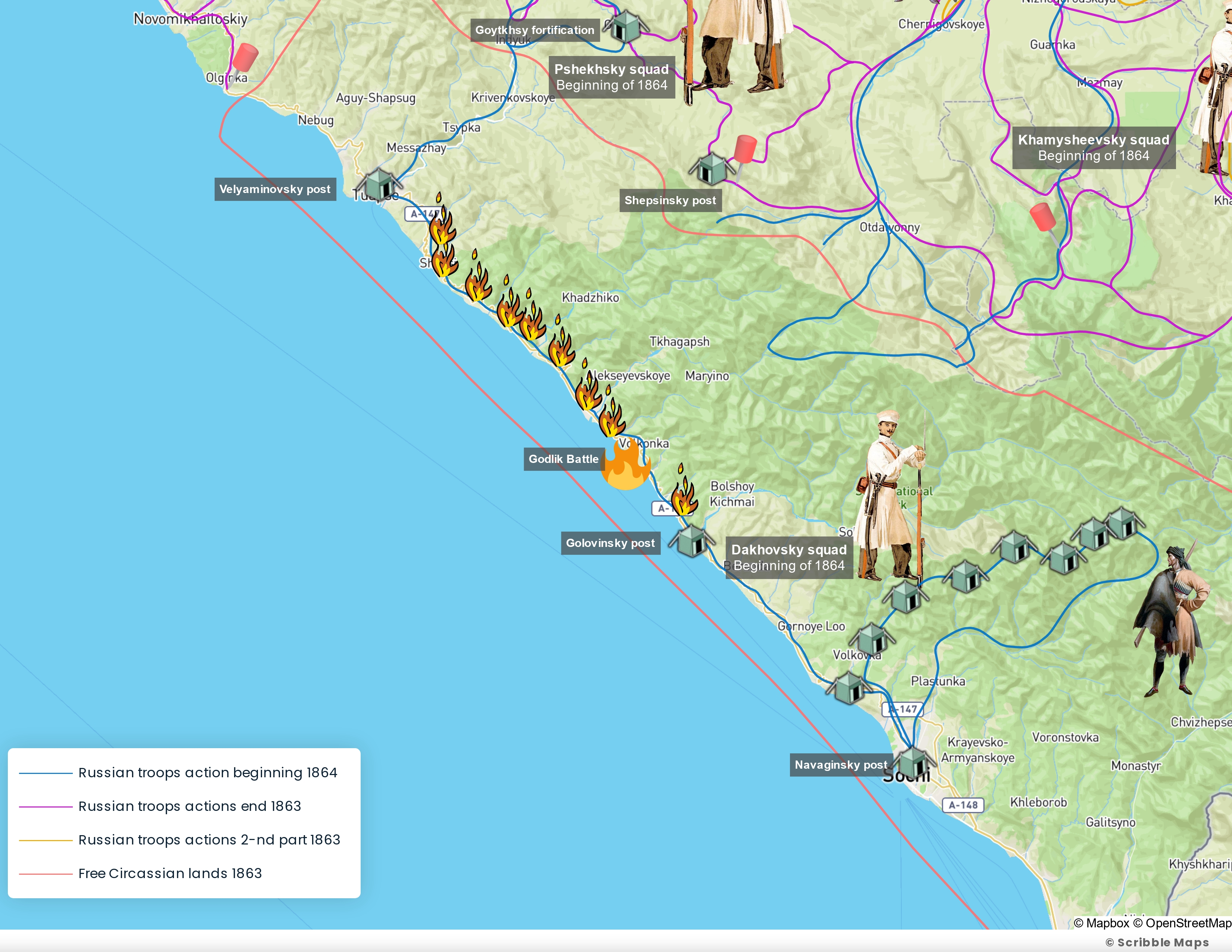

On February 21st, the Dahovsky detachment, consisting of 13.5 infantry battalions, 2 squadrons of dragoons, 3 hundred Cossacks, and 2 hundred native militia, along with 6 mountain guns, crossed the Pshish Pass. They descended first to the Chilipsi River and then to the Tuapse River, traveling the entire length of the latter on February 22nd and 23rd. They occupied the former Veliaminovskoye fortification at its mouth. Immediately upon the arrival of the troops at the coast, representatives of the societies on the southern slope, up to the Psezuapse River, showed submission and expressed unconditional loyalty.

Contemporaneously with these actions of the Dahovsky detachment, the actions of the Djubsky detachment were as follows: On February 19th, the detachment departed from the Grigoryevskoye fortification and, after crossing the Shebsh Pass, descended to the Tenginsky post by March 4th. They were later returned to the Grigoryevskoye fortification because, as events unfolded, there was no further need for their assistance in this area. The remaining forces of this detachment, not involved in the movement to the southern slope, after joint actions with the Pshekhsky detachment, remained at the Psekups mineral springs, where they worked on the road to the Chibiysky post.

With the commencement of military operations by the Dahovsky detachment at Tuapse and the clearance of the North Slope from natives, there were no more operations left for the Djubsky detachment. Therefore, on March 7th, after returning to the Grigoryevskoye fortification, it was disbanded. The troops that made up this detachment were partially sent to the Natukhaisky district to strengthen the military resources there, and part of them joined the Pshekhsky and Dahovsky detachments.

Thus, by the end of February 1864, the program of military operations in the Kuban region, within the limits specified by the Supreme Decree of May 10, 1862, regarding the settlement of the western part of the Caucasus Range foothills, had been implemented. The resettled part of the Northern slope and the Southern slope of the Tuapse Valley began preparations for military colonization, which, as mentioned earlier, was intended to firmly connect the settlements established along the eastern coast of the Black Sea with the stanitsas built along the Belaya, Kurdzhips, Pshekha, and Pshish rivers.

Following these events from the end of February, the Dahovsky detachment worked on developing the road from the mouth of the Tuapse River up the right bank of the river to the Goytkh fortification. They also established a post at the site of the former Veliaminovskoye fortification.

The Khamysheevsky and Malo-Labinsky detachments in January and February engaged in the same activities as at the end of 1863. In addition, on February 22nd, a part of the Malo-Labinsky detachment conducted reconnaissance of the road to the Umpyr tract.

In January and February, flying columns, gathered from different parts of the region, carried out the following movements: from January 21st to February 19th, from the Khablskaya stanitsa through the mountains adjacent to the yurts of the advanced stanitsas of the Laba Cossack regiment; from February 15th to February 20th, from the Samurskaya stanitsa to the Tubin Society; and from February 5th to February 27th, the coastal valleys between Mezib and the Syunskiy post were explored, where some Natukhais families had moved during the winter. In addition, a flying detachment composed of the Bzhedug militia expelled 2.5 thousand impoverished Abadzekhs to Kuban from February 11th to February 17th. These Abadzekhs remained after the general expulsion of this people between the lower reaches of the Pshish and Psekups rivers.

It was previously mentioned several times that the natives, under the influence of the detachments, either moved from their places of residence according to their own wishes or were expelled to our territories in the designated settlement zone of land. Some of them also went to various points on the coastal areas for transportation to Turkey. Some of these natives, after exhausting their food supplies at the coast, gradually began returning to their former places of residence in the mountains. To remove them from there, light cavalry and partisans were sent. Upon receiving positive information about the presence of such natives in the peaks of Psekups, Shapsugo, Il’, Afips, Ubin, Khabl’, and Pshada, four separate light columns were sent from the Grigoryevskoye fortification and Khablskaya stanitsa to these places. They cleared these areas of the returning mountaineers, either capturing or disturbing them, and prevented them from returning. In order to prevent individuals from settling in the mountains, half a battalion of infantry, along with a detachment of Cossacks, were stationed in the upper reaches of the Psekups in April. They observed the mountainous area between the upper reaches of the Psekups and Shebsh on the North, Shapsugo and Djuba on the Southern slopes, and conducted daily searches with small squads and patrols. This finally cleared the region of the returning natives and prevented new ones from coming back.

In the previous chapter, it was mentioned that with the final occupation of the entire Kuban region by the troops, the upper reaches of the Pshekha and the upper tributaries of this river remained unexplored. There, remnants of the mountain Tubin society still resided. To cleanse this last refuge of rebellious mountaineers, on March 28th, a concentration of 5 infantry battalions, with 2 mountain guns, was made in the Prusskaya stanitsa from the Pshekhsky detachment. They proceeded through the Tubin society and removed all the remaining natives. With the assistance of a special flying detachment operating on the eastern side of the aforementioned society, they reached the Pshish Pass on April 13th, where in the upper reaches of the Psezuapse River, a small wild society called Khakuchi was discovered. On the 14th, they crossed the Belorechenskiy Pass and on April 15th, they arrived at the Samurskaya stanitsa.

From the beginning of March, the Dahovsky detachment turned to occupy the region southeast of Tuapse. Advancing with several columns on March 4th along the Psezuapse River and clearing the space between this river and the Tuapse River of natives, the detachment moved further on March 18th along the Shakhe River. They dispersed the gathering of the Ubykhs and Akhchipskhuvs on the Godlik River and occupied the former Golovinskiy fortification on the 19th. Taking advantage of this rapid success, the troops did not stop at the Shakhe River but continued forward. On March 25th, they settled at the Sochi River, capturing the former Navaginskiy fortification. On April 2nd, the last Shapsug societies, the Ubykhs, Akhchipskhuvs, and Jigets, submitted unconditionally.

By April 15th, the detachments were in the following positions: The Pshekhsky detachment, after returning to Khadyzhi after crossing the Pshekha and Belorechenskiy Passes, continued to widen the road that had been constructed in the Pshish Valley up to the Goytkh fortification. In addition, from time to time, light columns were sent to the side gorges to expel returning natives.

The Malo-Labinsky detachment opened up wheeled traffic along the Shakhgireyevskoe Pass, almost to the Maliy Rashtaist area.

The Khamysheevsky detachment, having completed the wheeled road to the Khamyshey fortification and the defensive fences of this fortification, developed a pack road up the left bank of the Belaya River to the Guzeripl’ post.

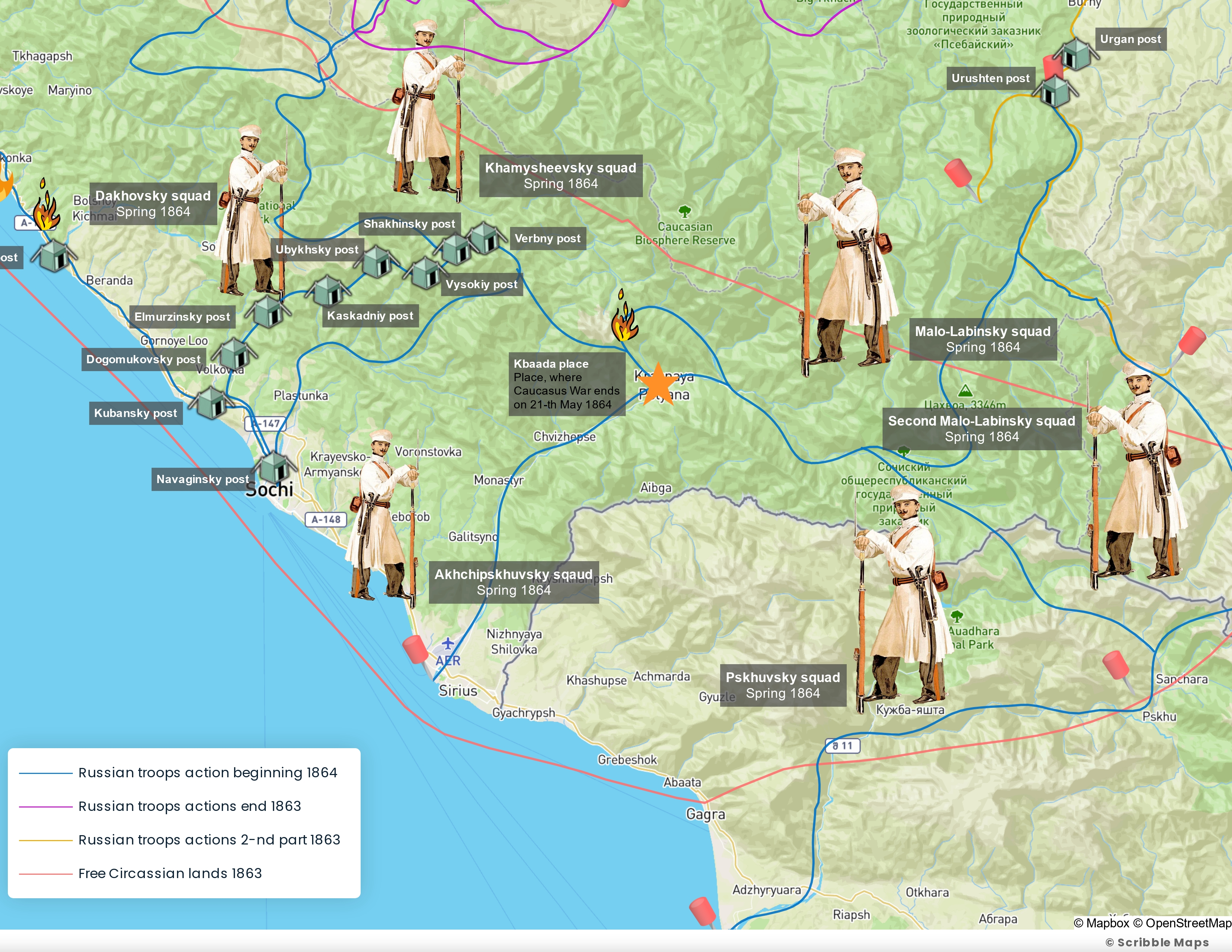

The Dahovsky detachment carried out work in the Tuapse Valley and on the newly fortified Ubykh border line established at the beginning of April, which extended from the mouth of the Dagomys River to the sources of the Shakhe River. In the Tuapse Valley, the work consisted of laying a pack road along the right bank. Eight posts were established on the Ubykh border line, namely: Kubanskiy, Dogomukovskiy, Elmurzinskiy, Kaskadniy, Ubykhskiy, Vysokiy, Shakhinskiy, and Verniy. Two bridges were built, one across the Dagomys and the other across the Shakhe River (note: and in some places, pack roads were developed along the line). In addition, from the 14th to the 17th of April, a survey of the area between the border line and the Sochi River was carried out.

With the detachments in these positions and the work mentioned above, in the second half of April, according to the orders of His Imperial Highness, preparations were made for the formation and deployment of three columns. These columns were to coordinate their actions with the actions of the troops of the Kutaisi Governorate, which were being sent for the same purpose from Djigeti and Abkhazia to the Psakhe and Akhchipskhu societies. This marked the beginning of the final subjugation of Western Caucasus.

Actions of the Adagumsky Detachment in 1864

Actions of the Adagumsky Detachment in 1864

Actions of the Pshekhsky and Khamysheevsky Detachments in 1864

Actions of the Pshekhsky and Khamysheevsky Detachments in 1864

Actions of the Dakhovsky Detachment in 1864

Actions of the Dakhovsky Detachment in 1864

In these plans, the right column (Khamysheevsky detachment), intended for actions in conjunction with the Dahovsky detachment, was reinforced to 5.5 battalions of infantry, with one hundred Cossacks and 2 mountain guns. The middle and left columns (Malo-Labinsky detachment) were reinforced to 12 battalions of infantry and two hundred Cossacks, with 2 mountain guns, and initially concentrated in the Maliy Rashtaist area. By the end of April, all these columns had gathered their troops in full force and, according to the orders of the Commander-in-Chief, began forced labor: the first column developed a packhorse trail from the Khamysheisky fort upstream along the Belaya River to the mouth of Guzeripl, and from there, along this last river to the Belorechensky Pass, where they established contact with the Dahovsky detachment in early May; the middle column was laying a packhorse trail from the Maliy Rashtaist area to the Psegashko Pass, and after crossing this pass, it was supposed to enter into immediate contact with the Akhchipskhuvsky detachment, which was operating from the seacoast upwards along the Mzymta River; finally, the left column was supposed to open a route through Umpyr and Zaagdan to the pass from Bolshaya Laba to Bzyb, and after crossing this pass, it was to operate in conjunction with the Pskhuvsky detachment, which was supposed to advance from Abkhazia to the Bzyb peaks near the Pskhuv society. The complete inaccessibility of the Bolshoy Labynsky Pass in April and May forced a change in the movement of this column; the majority of the troops were turned, along with the middle column, towards the rapid development of the road to the Psedashko Pass, while a part continued to build the road to Umpyr and further to Zaagdan.

The Psekhsky detachment remained in the Psekh Gorge to complete the road through this gorge and open a wheeled communication route through the Psekh Pass. By May 15th, almost the entire road through the Psekh Gorge was completed, and a packhorse trail was developed through the pass.

The 4 infantry battalions and 24 Cossack hundreds that became available as a result of this distribution and the border order were handed over to the punitive Ataman of the Kuban Cossack Host in the second half of April for the resettlement, with their help, of settlers from beyond the Kuban colonization border of 1864 and the development of communication where necessary. During May and June, these troops settled 52 stanitsas in the area between Il’ and Pshish, on the northern slope, to connect the Abinsky with the 26th regiment and on the southern slope from Gelendzhik to Tuapse. All the settlers designated for resettlement beyond the Kuban had arrived at their destinations and started building their farms.

In mid-May, orders were sent out to concentrate the middle column and a part of the Dahovsky detachment in the center of the Akhchipskhuvs land of Gbaada, where, by that time, the Pskhuvsky and Akhchipskhuvsky detachments were also supposed to arrive. On May 15th, the middle column arrived in Gbaada, followed by the Dahovsky and Pskhuvsky detachments, and on the 20th of the month, His Imperial Highness the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Army arrived with the Akhchipskhuvsky detachment. Except for the Pskhuvsky detachment, which encountered strong resistance when occupying the Aibga society, the other detachments had almost no clashes and, inviting the natives to come to the seashore, saw in them a readiness to accept the invitations. Thus, being convinced of the submission of the last natives, a thanksgiving service was held on May 21st, when the four aforementioned detachments were assembled, to commemorate the conquest of the Western Caucasus. On the same day, the Dahovsky detachment moved to the Sochi River, the Akhchipskhuvsky detachment to the mouth of the Mzymta, and the Pskhuvsky and middle columns began the final resettlement of the last Akhchipskhuvs.

On May 25th, upon the arrival of the Akhchipskhuvsky detachment at the mouth of the Mzymta River, His Imperial Highness saw fit to temporarily assign this detachment to the forces of the Kuban region to be directed, along with other forces, towards the final cleansing of the lands of the Jiget and Akhchipskhuvs natives. Additionally, the Pskhuvsky detachment was tasked with clearing the lands of the Pskhuv people. Immediately upon receiving this order, the troops of the Akhchipskhuvsky detachment were incorporated into the Dahovsky detachment and began their mission. In the first half of June, the Jigets, Akhchipskhuvs, Pskhuvs, and Aibga natives were resettled from their places and sent to Turkey. The troops of the former Akhchipskhuvsky detachment returned to their positions, and the Dahovsky detachment began working on the road up the Mzymta River, heading towards the Psegashko Pass, to meet with the Malo-Labinsky detachment.

Thus, the resettlement of the natives of the Western Caucasus was completed. In the first half of June, the majority of them were sent to Turkey, with only a few isolated mountain families, numbering one, two, or three, who had not managed to leave for Turkey. Additionally, several dozen families known as the Hakuchey continued to occupy the upper reaches of the Psezuape River. Due to lack of time and the insignificance of the Hakuchey, no urgent actions were taken against them. In the first half of June, separate columns from the Pshekhsky and Dahovsky detachments were sent to deal with this society. For this purpose, a portion of the Dahovsky detachment was transferred to the last detachment, including the Khamysheevsky detachment with 3.5 battalions of infantry. The remaining forces of this last detachment were redirected to develop the road from the Dahovskaya stanitsa upstream along the Sohra River to two stanitsas settled on this river in the previous year. After this, the Khamysheevsky detachment, having completed its mission, was disbanded.

By July 1st, the forces of the Kuban region were allocated for military-road works along the Malaya Laba, Mzymta, Pshekha, in the former Tubinsky society, and further to Hakuchi, Pshish, Tuapse, Psekups, and Pshada.

The actions of Russian detachments in April-May 1864, during the final stage of the war

The actions of Russian detachments in April-May 1864, during the final stage of the war

This is the general picture of the course of military operations in the Western Caucasus, as a result of which hundreds of thousands of local residents were expelled beyond their homeland, and tens of thousands of people perished. Mapping and comparing forces allow us to see a picture more reminiscent of a pogrom and total displacement than a classical war. The resistance was so weak and swiftly broken that there was no need even to speak of a partisan war.

To fully understand the context of these events, we will address in separate articles the questions of the course and consequences of the Circassian (Adyghe) expulsion from their lands and the organization of life for those who remained, issues related to prisoners of war and exiles, and also the equally important matter of trade balance and the assortment of barter trade that existed in the 20 years leading up to these events. The latter is crucial for understanding how the Russian Empire systematically constructed the ideological stereotype of the savage and predator in the average indigenous inhabitant of the Western Caucasus.

Read about this in the next article