In my previous article, I mentioned the importance of the issue of trade relations of the Circassian society with the outside world. There exists a stereotypical notion of the supposed absence of any trade among the Circassians, except for slave trading. The myth of their ancestors' mass involvement in this shameful activity is very persistent and is used today both in academic circles and for propaganda purposes. In the past, it was even more prevalent, and even 19th-century scholars like Leonid Lulye, who admired the language and culture of the people, indulged in lengthy and detailed stories about the local inhabitants' perpetual addiction to slave trading, deeply rooted over the centuries.

However, a detailed examination of trade documents from various years shows that although slave trading was present in Circassian society, it was far from being the main activity and was not widespread. It can be compared to the modern black market of antiques – large, very profitable, but also very risky. Just as only rich aristocratic families participated in the slave trade, only influential and wealthy people are involved in the underground antique market. Without resources, survival in it is impossible. Let's try to clarify this issue and understand the scale of trade activities in Circassia in the 19th century. First, let's find out what goods were sold and bought by the Circassians. We will be assisted by the statistics of goods exchange at four exchange courts along the Kuban River (Black Sea coastline), collected for the period from August 28, 1849, to January 1, 1850, from the archive of the National Historical Archive of Georgia, Fund 4, Inventory 5, File №91 "On the Issue of Exchange Trade of the Black Sea Cossack Army with the Trans-Kuban Circassian Tribes."

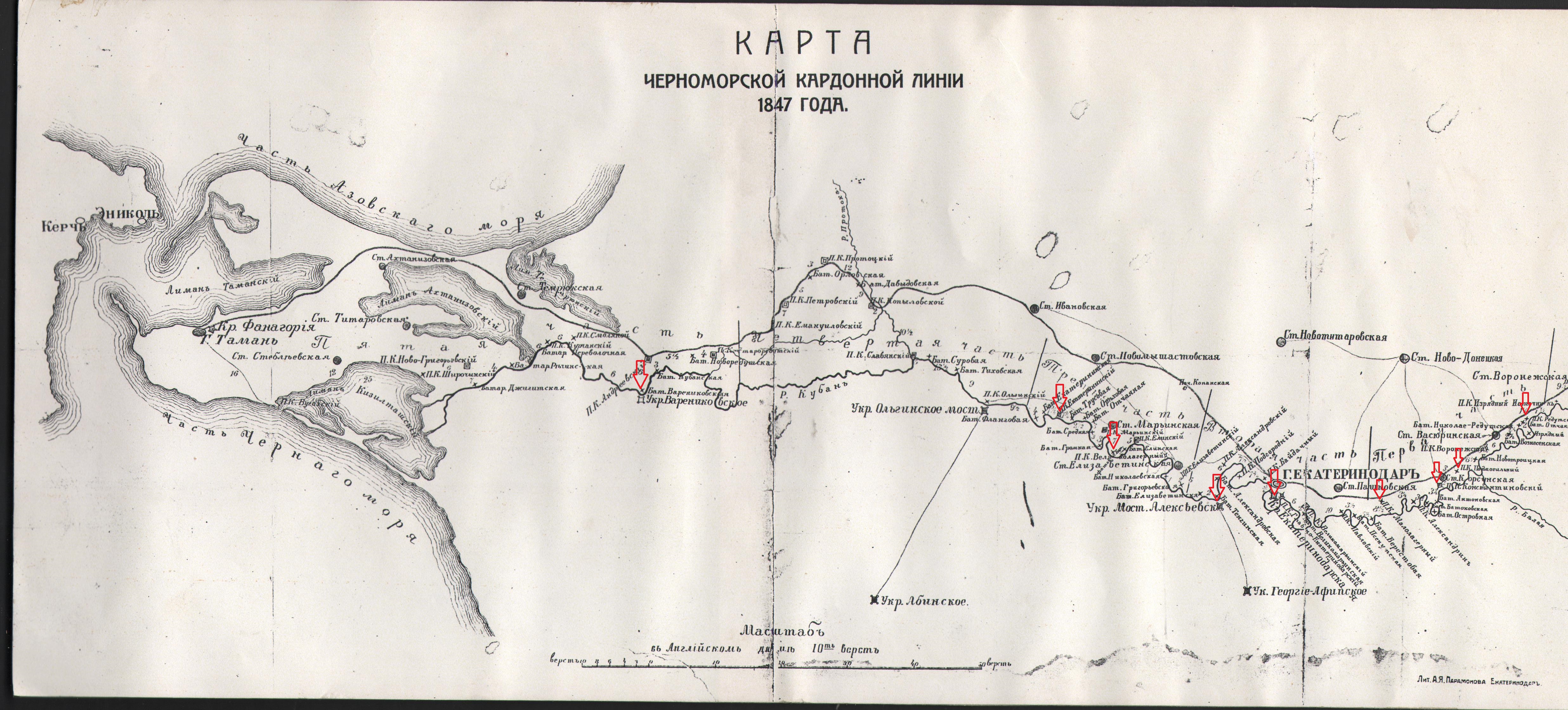

Along the Black Sea coastline, until 1849, there were seven exchange courts, scattered over 105 versts (approximately 112 kilometers) and divided into three parts. In the first part, courts operated at the Redutsky (sometimes replaced by the Podmogilny post), Konstantinovsky, and Malolagerny posts (a total of 20 versts or 21.3 km). Next, 20 versts to the west (or 21.3 km) in the second part, at the Ekaterinodarskaya fortress and Alexeyevsky posts (a total of 10 versts or 10.6 km). And further, 25 versts to the west (26.67 km), in the third part, at the Velikolagerny and Ekaterinensky (sometimes replaced by the farther Varenikovsky) posts (a total of 30 versts or 32 km).

Map of the Barter Trading Posts along the Black Sea Cordon Line in 1849.

Map of the Barter Trading Posts along the Black Sea Cordon Line in 1849.

By the end of 1849, all these exchange courts were evenly distributed along the entire length of the river at 4 different sections, each recording separate trade operations. They all covered a distance roughly between the modern Voronezhskaya stanitsa in the east and Fedorovskaya stanitsa in the west (near the Fedorovsky hydraulic structure) of the Krasnodar region, sometimes stretching further west to the modern Varenikovskaya stanitsa.

Based on the data from the tables (link), what conclusions can we draw?

Total Volume of Barter Trade at the Trading Posts along the Black Sea Cordon Line in 1849.

Firstly, the exchange of goods at the exchange courts was not measured in any stable currency. Circassians brought their goods for exchange, and the evaluation of the traded goods occurred during the transaction, based on intuition and visual assessment, depending on demand. Therefore, we cannot assess the value and the total volume of trade in the classical sense of the word. However, we can look at the total mass of exchanged goods to estimate the volume of trade and understand which of them were in highest demand. In this article and the accompanying charts, various units of product volume measurement have been converted to a unified modern format - liters, kilograms, pieces, in accordance with the measurement calculator.

Secondly, there is a noticeable imbalance in the volume of supplies from Circassia. However, this does not mean that the Circassians produced more than they purchased. Below, we will look at the composition of the exchangeable products, from which it will become clear that their production value was different. Roughly speaking, the Circassians exchanged products of primary agricultural production, minerals, and raw materials not only for food products (of a different type) but also for much more expensive manufactured products. The total volume of trade units for the 4 months of 1849 amounted to 2,418,613 units of goods.

From this total mass, the main category of goods consists of agricultural products, accounting for the lion's share of 1,854,446 units, nearly 75% of all products. At the same time, food products were also purchased by Circassians. In total, they acquired 438,686 units of food products in exchange for 1,415,760 units sold to the Russian authorities.

Unique goods supplied by Circassians included various types of raw materials, such as leather, wood, various furs, etc. Such types of goods were not exchanged in return. Circassians supplied the Russian authorities with a total of 153,058 units of raw goods. In turn, manufactured goods, although not in large quantities, were supplied to each other by both sides, albeit not in equal quantities and in different assortments. Circassians supplied the Russian authorities with 160,302 units of various manufactured goods, mainly clothing, garment and weapon accessories, and low-quality clothing materials. In return, they acquired 250,807 units of manufactured goods, predominantly various types of medium and high-quality fabrics, furniture, and utensils.

Thus, we can make the first conclusion – trade at the exchange courts was most often conducted with agricultural products and to a lesser extent involved the exchange of manufactured goods made of fabrics and furniture. A separate category was the supply of raw materials by Circassians, such as wood and skins.

Now let's take a closer look at the composition of the goods exchanged by the parties at the barter yards.

Categories of Goods in the Structure of Exports from Circassia in 1849.

Categories of Goods in the Structure of Imports to Circassia in 1849.

In the export chart from Circassia, the production of the famous Circassian gardens, which bore fruit all year round, leads by a significant margin in terms of volume. This primarily includes pears and apples (sour apples). In third place among the leaders is oats, a primary feed product for horses on both sides of the border.

After these three, much smaller volumes of rabbit skins and wood (the most popular log option being 17.78 cm in diameter) were purchased in Circassia, as well as ready-made palisades for fences and metal hoops for fastening various materials.

In the import chart to Circassia, two types of goods almost completely dominate - salt and sewing needles. However, it should be noted that the per-unit count of needles greatly distorts the picture, and if they were measured by weight, it might be different. Nonetheless, the overwhelming volume of salt supplies still skews the overall picture. If we exclude needles and salt from the calculations, we see an almost uniform distribution of the volumes of various types of fabrics purchased by the Circassians, such as calico, unrefined calico (mitkal), canvas, aladja, bon, nainsook, and linen. Silver threads (for embroidery), combs, and wooden cups were also equally popular items.

What is special about these charts?

Firstly, there is a noticeable discrepancy in the supplies of key exchange goods, which are traditionally considered to be salt and various types of timber. We see that salt is the largest volume of goods purchased in Circassia, where it was always in short supply. Salt is needed not only for household and kitchen use but also in large quantities for livestock, which suffers greatly without it. With the arrival of the Black Sea Cossacks in 1791-92, the largest and oldest salt deposits in Taman and the Azov region became inaccessible to the local Circassian population for the first time in many centuries, as they were privatized by the newcomers. Since then, salt has become not only the main product of exchange but also a serious lever for blackmail and pressure from the Russian authorities. The chart reflects a reality that corresponded to the descriptions of contemporaries.

On the other hand, the right bank of the Kuban, mostly steppe, constantly needed construction timber. It is believed that timber was the main commodity for exchange for salt. However, from the charts above, it can be noticed that the volume of timber supplied barely exceeded 70-80 thousand units. To this, perhaps, we can add the palisade in the amount of 53 thousand units. This volume in no way correlates with the 435 thousand poods of salt, which in any case turn out to be much more expensive than the volume of timber supplied. Certainly, this situation can be attributed to the lack of need for timber among the Cossacks during the specific period of the second half of 1849. Nevertheless, this question requires further research in the future.

Secondly, some trends related to the extensive development of horticulture and livestock breeding in Circassian society and a keen interest in Russian and world contemporary fashionable fabrics are confirmed. As everywhere, Circassian women wanted to look beautiful and modern.

For a more detailed distribution of the volume of purchase and sale of goods at the exchange yards, you can see these charts:

Top Export Goods from Circassia in 1849.

Top Import Goods to Circassia in 1849.

Now let's try to understand the darker side of the Circassian economy - the slave trade.

As I have already mentioned, slave trading was the domain of privileged individuals from the aristocracy or intermediaries. According to estimates by the notable researcher of slavery in the Caucasus, Mikhal Shmigel, in the 19th century, approximately 10-12 thousand people, mostly women and children, were annually exported from the Caucasus to Turkey. This was during years when there were no major military actions. A person was sold for between 200 to 800 rubles, roughly equivalent to 1-3 years of a Russian officer's salary at that time. They were then sold for up to 1500 rubles. Therefore, the profit exceeded the expenses by at least 2-5 times, and it was possible to earn a lifetime's income from just one deal, but at a very high risk.

Of course, outsiders were not part of this "business". However, it is important to consider another very important fact - the majority of those sold did not consider themselves slaves, nor did the traders themselves. If they were not war captives, the sales transactions were voluntary.

The fact is that in the Caucasus, there was a long-standing culturally conditioned tradition. Girls in the family were considered (and in some places still are) a burden, as they do not bring any addition to the family and require a dowry. Girls leave for their husband's family after marriage, which benefits from this addition. The preference was given to boys, and girls faced an unwelcome fate in their native lands. Hence the desire of senior relatives to arrange the daughter's life as profitably as possible with minimal losses for the family. Thus, the matchmaking ritual turned into a kind of business with marriage agents, in the form of "slave traders," who paid the family what was essentially a "wedding ransom by proxy." The girl thus sent away was transported to the Ottoman Empire, where her "bridegroom bought her from the intermediary," typically a wealthy Ottoman official or even the sultan. The girl entered his harem, became an official wife with all rights and duties, and could even help her compatriots in the future. Of course, the groom might turn out to be a villain, but girls were not protected from this at home in the case of a classic wedding. On the other hand, only wealthy people who could also secure the fate of the new wife could afford to buy such a girl.

The same applied to children who ended up in households or in military academies for service. In the Ottoman Empire, there were restrictions on the period of slavery for a bought person, who after its expiration gained the rights and duties of a subject of the sultan and had the right to own property and choose their fate independently.

Thus, the classic image of slavery and sale into "Turkish captivity" does not quite correspond to the truth. Especially in comparison with the bleak serfdom in Russia, which was mimicked as a godly and legal affair and modestly called "dependency." Thousands of people who ended up in Turkey through slave traders, in fact, received an opportunity to arrange their lives better than at home.

However, this certainly does not apply to those who were captured by force and sold. These included not only Slavs and Georgians, who were often the target of raids, but also among the Circassians themselves, since internal enmity among different societies did not differentiate between friend and foe, and residents of a village feuding with another village could be taken captive in a momentary conflict.

For more detailed information on how the slave trade was organized and what fates awaited those sold in this way, you can read the wonderful book by the Turkish researcher Elbrus Aksoy "White Slaves." Unfortunately, it is only available in Turkish at the moment, but its English and possibly Russian translations are expected soon. I will inform you as soon as the translation is ready!

Elbruz Aksoy "White Slaves"

Elbruz Aksoy "White Slaves"

Let's summarize. The report on the work of the barter yards on the Black Sea border line in 1849 shows that the largest volume of goods concerned the supply of food and agricultural products - grains and fruits. The key items of purchase were salt for Circassia and various forms of timber for the Russian side, although the latter was significantly lesser in volume. To a lesser extent, there was an exchange of manufactured goods; Circassia supplied various raw materials, and in return, they received various fabrics, needles, threads, dishes, and furniture.

Regarding the slave trade, despite its extensive volume, it was mostly based on voluntary beginnings with the assistance of "wedding agents." It played a role in arranging marriages for girls with wealthy Turkish families, as traditionally girls were economically burdensome for the family.

In the next article, we will look at the last question in the series about the Circassian exodus - the fate of war captives from the Caucasus in the Russian Empire.